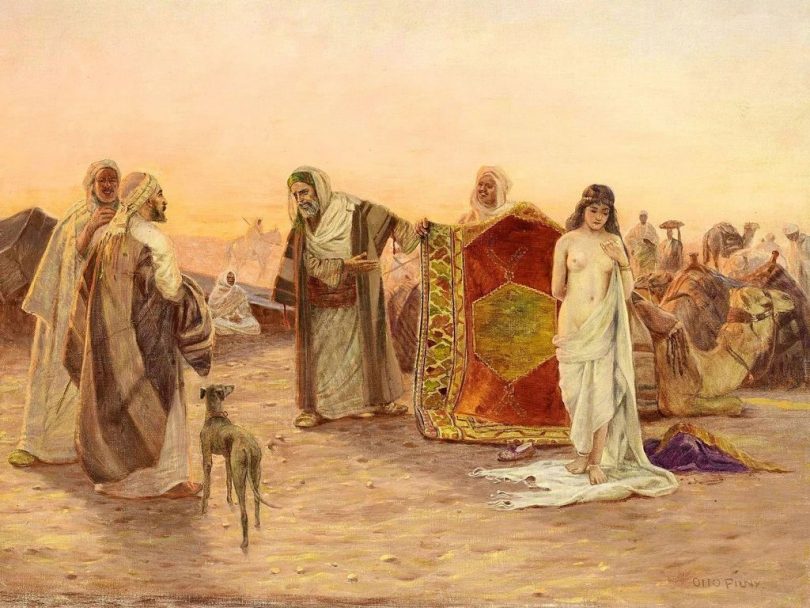

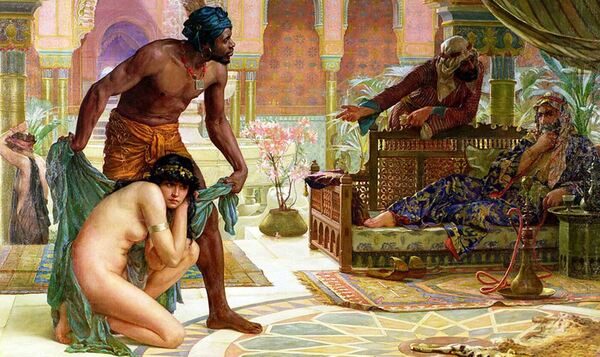

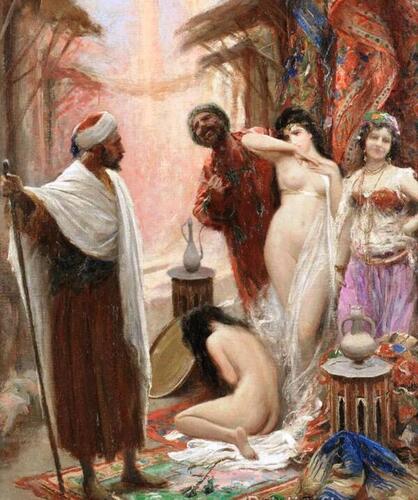

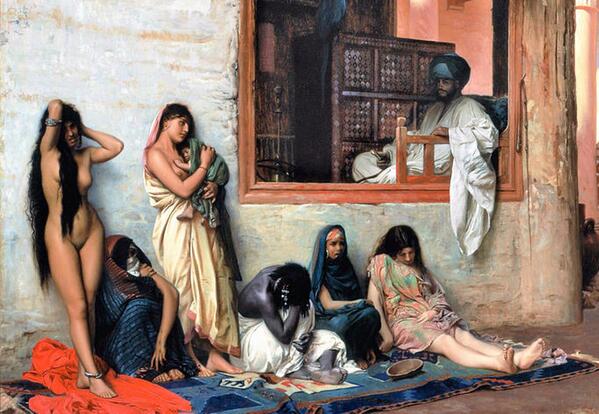

Last year, a political party in Germany provoked controversy when it used the following painting in its election campaign to illustrate one of the reasons it was against immigration.

Painted in France in 1866 and titled “Slave Market,” the painting was described as “show[ing] a black, apparently Muslim slave trader displaying a naked young woman with much lighter skin to a group of men for examination,” probably in North Africa.

The Alternative for Germany party (AfD) put up several posters of this painting with the slogan, “So that Europe won’t become Eurabia.” Many on both sides of the Atlantic were triggered by this usage; even the American museum where the original painting is housed sent AfD a letter “insisting that they cease and desist in using this painting” (even though it is in the public domain).

Objectively speaking, the “Slave Market” painting in question portrays a reality that has played out countless times over the centuries: African, Asiatic, and Middle Eastern Muslims have long targeted European women — so much so as to have enslaved millions of them over the centuries (see Sword and Scimitar for copious documentation).

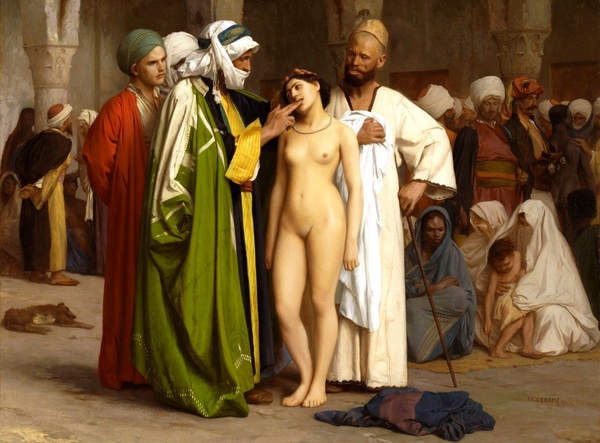

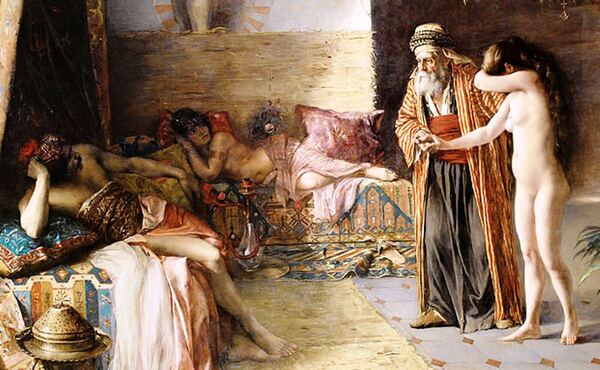

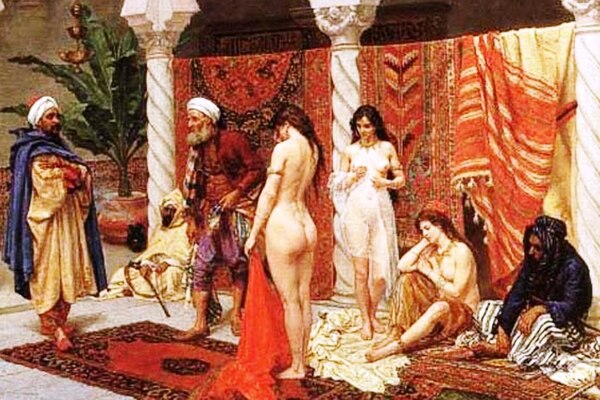

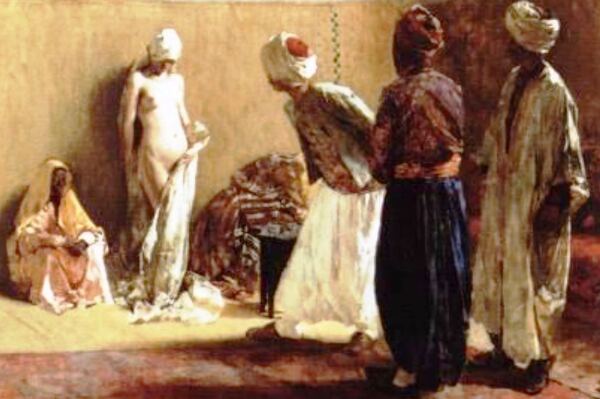

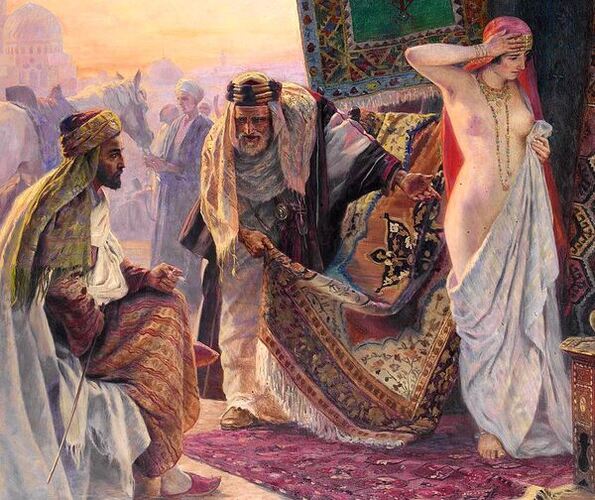

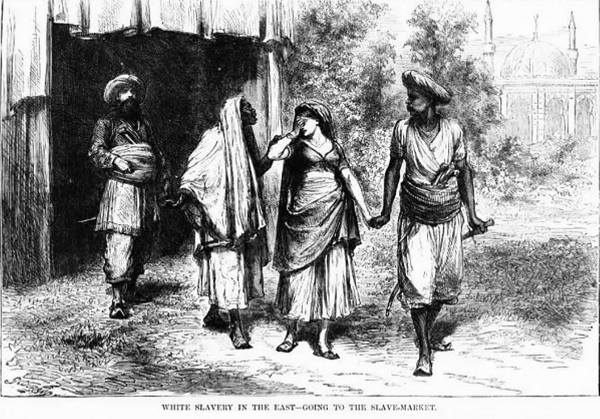

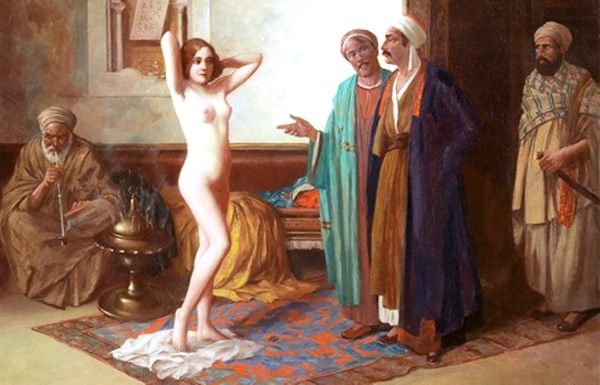

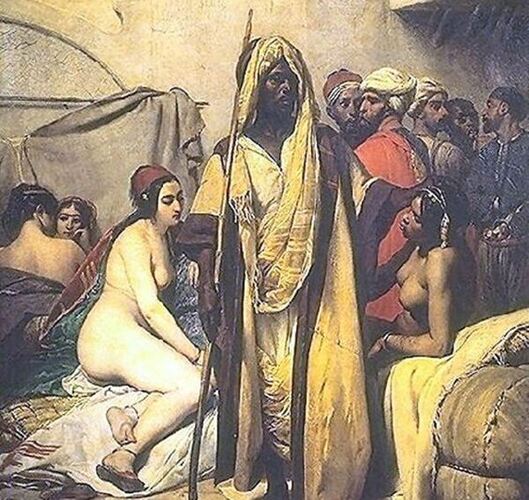

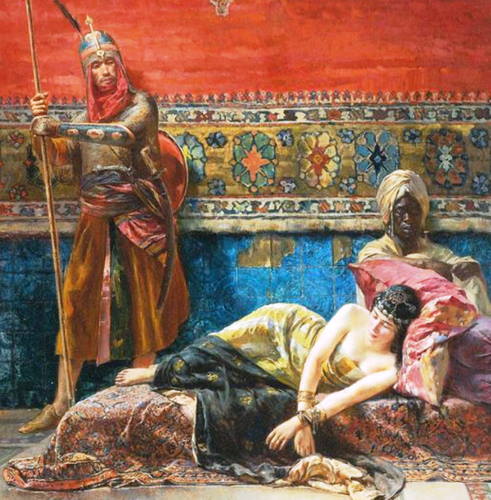

As it happens, there is something else — another medium besides writing — that documents this reality: countless more paintings than the one in question concerning the abduction, trafficking, and sexual enslavement of European women, all of which further underscores the ubiquity and notoriety of this phenomenon. Indeed, this was such a well known theme that many nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artists and painters specialized in it, often based on their own eyewitness accounts. (As one art gallery puts it, “Many … of the most important painters did travel [to the Muslim world] themselves, and what they painted was based on the sketches they had made while they were there[.])

Below are just 20 such paintings (there are many more). Aside from noting the artist’s name; year of painting; and, where possible, title—information which is often difficult to ascertain — I’ve limited my remarks to important asides and clarifications, mostly in the first few paintings, leaving the rest to speak for themselves. They follow.

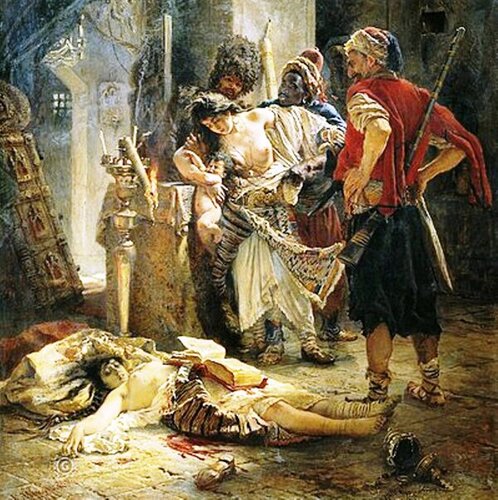

“The Bulgarian Martyresses,” by Konstantin Makovsky, 1877. It depicts events from a year earlier, when Ottoman irregular soldiers (the so-called bashi-bazouks or “crazy heads”) raped and massacred the Christian women of Bulgaria and their children. American journalist MacGahan, who reported from Bulgaria, wrote the following of this incident: “When a Mohammedan has killed a certain number of infidels he is sure of Paradise, no matter what his sins may be. … [T]he ordinary Mussulman takes the precept in broader acceptation, and counts women and children as well. … [T]he Bashi-Bazouks, in order to swell the count, ripped open pregnant women, and killed the unborn infants.”

“The Abduction of a Herzegovinian Woman,” by Jaroslav Čermák, 1861. From the museum’s official description: “Disturbing and extremely evocative, it depicts a white, nude [and pregnant?] Christian woman being abducted from her village by the Ottoman mercenaries who have killed her husband and baby.”

Raymond Ibrahim, author of Sword and Scimitar: Fourteen Centuries of War between Islam and the West, is a Shillman Fellow at the David Horowitz Freedom Center, a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the Gatestone Institute, and a Judith Rosen Friedman Fellow at the Middle East Forum.

The Muslim demand for, in the words of one historian, “white-complexioned blondes, with straight hair and blue eyes,” traces back to the prophet of Islam, Muhammad, who enticed his followers to wage jihad against neighboring Byzantium by citing its blonde (“yellow”) women awaiting them as potential concubines.

For over a millennium afterwards, Islamic caliphates, emirates, and sultanates—of the Arab, Berber, Turkic, and Tatar variety—also coaxed their men to jihad on Europe by citing (and later sexually enslaving) its fair women.

Accordingly, because the “Umayyads particularly valued blond or red-haired Franc or Galician women as sexual slaves,” Dario Fernandez-Morera writes, “al-Andalus [Islamic Spain] became a center for the trade and distribution of slaves.”

Indeed, the insatiable demand for fair women was such that, according to M.A. Khan, an Indian author and former Muslim, it is “impossible to disconnect Islam from the Viking slave-trade, because the supply was absolutely meant for meeting [the] Islamic world’s unceasing demand for the prized white slaves” and “white sex-slaves.” Emmet Scott goes further, arguing that “it was the caliphate’s demand for European slaves that called forth the Viking phenomenon in the first place.”

As for numbers, according to the conservative estimate of American professor Robert Davis, “between 1530 and 1780 [alone] there were almost certainly a million and quite possibly as many as a million and a quarter white, European Christians enslaved by the Muslims of the Barbary Coast,” that is, of North Africa, the telling setting of the painting. By 1541, “Algiers teemed with Christian captives [from Europe], and it became a common saying that a Christian slave was scarce a fair barter for an onion.”

With countless sexually enslaved European women—some seized from as far as Denmark, Iceland, and even Iceland—selling for the price of vegetables, little wonder that European observers by the late 1700s noted how “the inhabitants of Algiers have a rather white complexion.”

Further underscoring the rapacious and relentless drive of the Muslim slave industry, consider this: The United States of America’s first war—which it fought before it could even elect its first president—was against these same Islamic slavers. When Thomas Jefferson and John Adams asked Barbary’s ambassador why his countrymen were enslaving American sailors, the “ambassador answered us that it was founded on the laws of their Prophet, that it was written in their Koran, that … it was their right and duty to make war upon them [non-Muslims] wherever they could be found, and to make slaves of all they could take as prisoners.”

The situation was arguably worse for Eastern Europeans; the slave markets of the Ottoman sultanate were for centuries so inundated with Slavic flesh that children sold for pennies, “a very beautiful slave woman was exchanged for a pair of boots, and four Serbian slaves were traded for a horse.” In Crimea, some three million Slavs were enslaved by the Ottomans’ Muslim allies, the Tatars. “The youngest women are kept for wanton pleasures,” observed a seventeenth century Lithuanian.

Even the details of the “Slave Market” painting/poster, which depicts a nude and fair-skinned female slave being pawed at by potential buyers, echoes reality. Based on a twelfth-century document dealing with slave auctions in Cordoba, Muslim merchants “would put ointments on slave girls of a darker complexion to whiten their faces… ointments were placed on the face and body of black slaves to make them ‘prettier.’” Then, the Muslim merchant “dresses them all in transparent clothes” and “tells the slave girls to act in a coquettish manner with the old men and with the timid men among the potential buyers to make them crazy with desire.”

In short, outrage at the Alternative for Germany’s use of the “Slave Market” painting is just another attempt to suppress the truth concerning Muslim/Western history—especially in its glaring continuity with the present. For the essence of that painting—Muslim men pawing at and sexually preying on fair women—has reached alarming levels all throughout Western Europe, especially Germany.

Note: The historic events, statistics, and quotes narrated above—and more like them—are fully documented in Raymond Ibrahim’s Sword and Scimitar: Fourteen Centuries of War between Islam and the West.