By William Fischer. 2024-10.

Like many figures in the Bible, there’s not enough within the canon to have a firm, detailed biography of Mary, the virginal mother of Jesus. Her appearances in the gospels are relatively brief, even in passages concerning the birth of Christ. It’s in theology and biblical commentary that the episodes of the Bible involving Mary have been expanded and extrapolated, building up her role in the various Christian denominations.

That role is strongest within the Catholic tradition. Indeed, many Catholics have been asked if they worship Mary, and even some priests have been surprised by the strength of veneration for her in certain communities (per The Jesuit Post). Mary isn’t an object of worship in Catholicism — worship is owed to God alone — but she is looked upon as a pivotal figure in the life of Christ, as a partner in the redemption offered by Jesus, and as a being who can intercede with the Lord on behalf of sinners in prayer. But misunderstandings about her role make Mary a common weapon used by critics of Catholicism.

Even within the Catholic Church, the precise role of Mary is debated. Those debates are part of a long discourse. Throughout the history of Christianity, her relationship to Jesus and God, her relevance to Christian worship, and even her storied virginity have been subjects of controversy. Digging into the matter can reveal some surprising facts about Mary and interpretations of her. Here are some of the little-known details of the Virgin Mary.

It’s disputed whether Mary’s virginity is foretold in the Old Testament

A woman giving birth while still a virgin is a feat beyond all natural laws, and Mary’s birthing Jesus is counted as a miracle. Miraculous births weren’t exactly rare in the ancient world; religion, mythology, and folklore abound with children born of rivers, fathered by gods, and conceived by virgins. Critics of Christianity, and those who cling to the widely-discredited Christ Myth Theory, have tried to paint Mary’s conception of Jesus as cribbed from other mythologies. Osiris of Egyptian mythology and Attis from the Middle East are often cited as candidates for a proto-Jesus with a virgin birth, though the parallels between them and Jesus are thinner than supposed.

Not helping such theories is Christianity’s nature as an outgrowth of Judaism. And Jewish tradition does prophecy that the Messiah will be born of a virgin — at least, so the most common interpretation of Isaiah 7:14 goes. The Gospel of Matthew concludes that Mary’s birth is the fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy, which has long been translated from the Hebrew as: “The virgin will conceive and give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel.”

That translation has come under increased scrutiny in recent years. Per The Washington Post, Jewish and even Christian scholars now believe that the Hebrew “almah” should be read as “young woman,” not “virgin.” Some even feel that Isaiah wasn’t issuing a prophecy, but using a metaphor — that, in the time it would take for a boy to become a man, the enemies of Israel from Isaiah’s time would perish.

Jesus being born of Mary was an early rebuttal to the gnostics

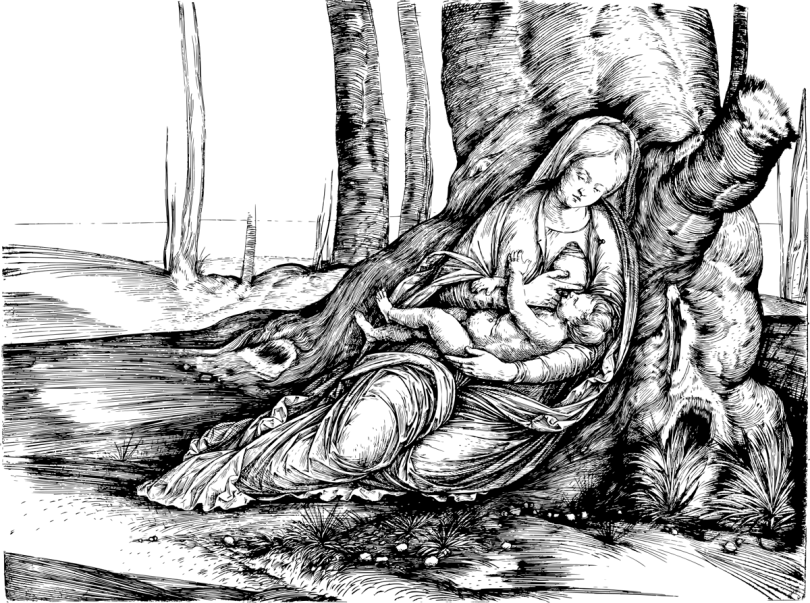

The birth of Jesus is only depicted in two of the gospels, Matthew and Luke. Likewise, the revelation to Mary that she would play mother to the son of God — known in Christianity as the Annunciation — appears in those two books. In Luke, the angel Gabriel comes to Mary and tells her that, because she is in the Lord’s favor, she will give birth to a son, heir to David and king eternal. Gabriel does not appear in Matthew, but it does see an angel come to Joseph to dissuade him from divorcing Mary after she is impregnated by the Holy Spirit.

Neither book goes into graphic detail on the actual birth, but Galatians 4 (via Bible Gateway) refers to Jesus as “born of a woman.” By that phrase, the canonical interpretation of the birth of Jesus is that he was literally birthed by Mary in typical mortal fashion, making Jesus fully human as well as divine. It also confirms Mary as the mother of Jesus, and her role as a mother is what is most valued and studied in Christian tradition.

But the insistence that Mary was truly, physically the mother of Christ also served as a counterargument to Gnosticism in the early church. Some gnostic sects posited that Jesus was not a mortal or physical being and that he was not born of Mary so much as he passed through her, like light through a prism. Confirmed parenthood, even if only one of the parents was human, would confirm Jesus to be fully human by an ancient understanding of the supernatural.

Mary is seen as a redemption for Eve

The ultimate power of Jesus in Christian thought is his redemption of all mankind. By some interpretations of Scripture, this puts Jesus on a parallel track to Adam, the first man; Adam’s sin and disobedience brought despair and death into the world, and Jesus’s obedience to God’s will brought salvation and eternal life. While only Christ is granted the power to redeem, the early Christian church carved out a similar parallel interpretation of Eve’s role in the Old Testament with Mary’s in the new (per Britannica).

Mary, obviously, had a different relationship to Jesus than Eve did to Adam. But Eve and Mary are both considered to have been virgins at the time of their most consequential acts — succumbing to temptation in Eve’s case, and accepting the responsibility of carrying and raising Christ in Mary’s. As Saint Irenaeus put it: “[It was necessary] that a virgin, become the advocate of a virgin, should undo and destroy virginal disobedience by virginal obedience.”

Within Catholicism, the parallels have been extended. Mary is believed by Catholics to have been born without original sin herself. And Mariology, the formal study of Mary, considers a view of Christ and his role incomplete without reckoning with the part Mary had to play.

Is she the mother of Christ or the mother of God?

someone not immersed in doctrine, the exact wording of a prayer or a specific title aren’t often worth fretting over. But the meaning behind those prayers and titles can carry profound implications within a faith. And there was significant controversy over how to refer to Mary in the early church, because of such a title’s implications on the nature of Jesus.

Per Britannica, Mary was titled “Theotokos” in the 3rd or 4th century. Theotokos translates to “God-bearer” or “mother of God,” and it is still used to refer to Mary in Orthodox Christianity (the Catholics aren’t the only ones who venerate Mary, though such traditions are less extensive in Orthodoxy). It’s been speculated that the term came into regular devotional use once the Council of Nicaea determined the divine nature of Jesus. But to label Mary as the Theotokos was to go beyond ascribing divine status to Jesus; it was to call him God himself.

On those grounds, Nestorius, patriarch of Constantinople, gave Mary a lesser title. He and his followers referred to her as the Christotokos, or Christ-bearer. It retained her, and Jesus’, significance without crossing a line they felt shouldn’t be crossed. But this, and other aspects of Nestorius’s theology, ran afoul of the Second Council of Ephesus in 431.

Mary also ascended into Heaven

Mary’s significance to Christianity is assured just by the nature of her being the mother to Jesus. Her part in the redemption of humanity, her sinlessness, and her virginity (whether it was perpetual or not) are more matters of controversy among denominations. And, as many aspects of her life are disputed by various churches, so is the nature of her death. The big question there concerns the Assumption of Mary: whether, upon reaching the end of her life, she ascended, body and soul, into Heaven as Jesus did.

The Assumption is accepted within the Catholic Church. Pope Pius XII declared it a dogma of the Catholic faith in 1950 (per Franciscan Media). The doctrine has been broadly traced back as far as the Book of Revelation, where Mary is seen as the most logical embodiment of “God’s people” in the battle of good and evil, and more specifically traced to eastern Christian beliefs of the 5th century. There is no body in either acknowledged tomb of Mary’s, and there are no acknowledged relics of hers.

But there has long been skepticism about the Assumption of Mary. Some have branded it a gnostic heresy, reflecting a rejection of the earthly aspect of Christ. And because it is not an event described in the Bible, many Protestant denominations reject the Assumption entirely.