Slaughter of the Knezes 1804

The Slaughter of the Knezes, refers to a massacre that was committed in January 1804, on the central square of Valjevo, Serbia. The victims were the most prominent Serbian nobles, titled Knezes (“local dukes”), of the Belgrade Pashaluk. They were executed by the rebel Dahias, the Jannisary junta that ruled Serbia at the time.[1]

The Dahias had taken power in the Pashaluk in defiance of the Sultan and they feared that the Sultan would make use of the Serbs to oust them. To forestall this they decided to execute all noble Serbs throughout Serbia. Notable victims were Aleksa Nenadović and Ilija Birčanin. The event triggered a widespread revolt which eventually evolved into First Serbian Uprising, aimed at putting an end to the 300 years of Ottoman occupation. According to contemporary sources from Valjevo, the severed heads of the murdered men were put on some sort of a public display in the central square to serve as an example to those who might plot against the rule of the Dahia.[1]

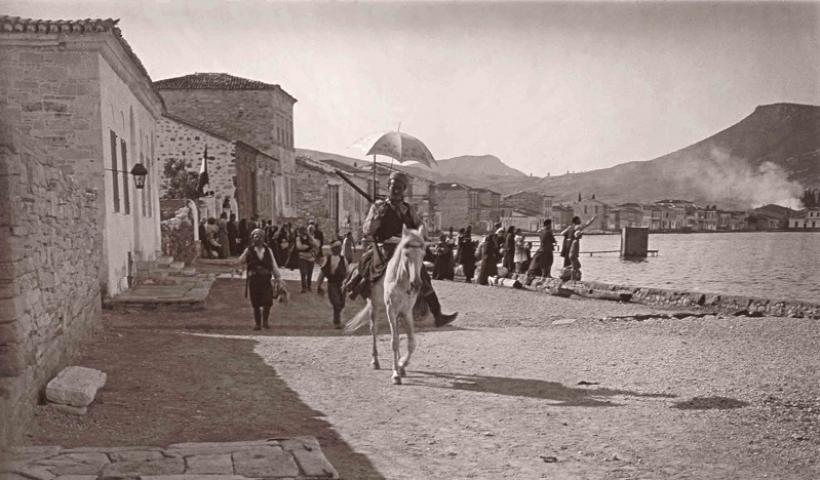

Great fire of Smyrna

The great fire of Smyrna or the catastrophe of Smyrna[1][2] destroyed much of the port city of Smyrna (modern İzmir, Turkey) in September 1922. Eyewitness reports state that the fire began on 13 September 1922[3] and lasted until it was largely extinguished on 22 September. It began four days after the Turkish military captured the city on 9 September, effectively ending the Greco-Turkish War, more than three years after the Greek army had landed troops at Smyrna on 15 May 1919. Estimated Greek and Armenian deaths resulting from the fire range from 10,000[4][5][6] to 100,000.[7]

Approximately 50,000[8] to 400,000[9] Greek and Armenian refugees crammed the waterfront to escape from the fire. They were forced to remain there under harsh conditions for nearly two weeks. Turkish troops and irregulars had started committing massacres and atrocities against the Greek and Armenian population in the city before the outbreak of the fire. Many women were raped.[10][11] Tens of thousands of Greek and Armenian men (estimates vary between 25,000 and at least 100,000) were subsequently deported into the interior of Anatolia, where many of them died in harsh conditions.[12][13][14]

The subsequent fire completely destroyed the Greek and Armenian quarters of the city; the Muslim and Jewish quarters escaped damage.[15] There are different accounts and eyewitness reports about who was responsible for the fire; a number of sources and scholars attribute it to Turkish soldiers setting fire to Greek and Armenian homes and businesses,[16] while pro-Turkish sources hold that the Greeks and Armenians started the fire to tarnish the Turks’ reputation.[17] Testimonies from Western eyewitnesses[18] were printed in many Western newspapers.[19][20]

Stara Zagora massacre against the weaponless civilians.

Stara Zagora is the sixth-largest city in Bulgaria. The Ottomans conquered Stara Zagora in 1371. 1877-07-31 is a tragic date in the city’s history. A major clash occured between the two belligerent armies of the Russian-Turkish Liberation War took place near Stara Zagora. The 48,000 Turkish army was launched on the town, which was merely defended by a small Russian detachment and a small unit of Bulgarian volunteers. After a six-hour fight for Stara Zagora, the Russian soldiers and Bulgarian volunteers surrendered to the pressure of the larger enemy army. The town then soon experienced its greatest tragedy. The armed Turkish army carried out the Stara Zagora massacre against the weaponless civilians. The city was burned down and razed to the ground during the three days following the battle. Incredibly sadistically were massacred 14,500 Bulgarians from the town and villages south of the town, encompassing all Bulgarian civilians with exceptions. Another 10,000 young women and girls were sold in the slave markets of the Ottoman Empire. All Christian temples were attacked with artillery and burned. The only public building surviving the fire was the mosque, Eski Dzhamiya, remaining even nowadays. This is possibly the largest and worst massacre documented in the Bulgarian history and one of the most tragic moments of the Bulgarians. While the people of Bulgaria lost this particular battle for Stara Zagora, they did ultimately win the war. Today, several monuments witness the gratitude of the Bulgarian people to its liberators.

Massacres of Diyarbakır (1895)

Massacres of Diyarbakır were massacres that took place in the Diyarbekir Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire between the years of 1894 and 1896. The events were part of the Hamidian massacres and targeted the vilayet’s Christian population – Armenians and Assyrians.

The massacres were initially directed at Armenians, instigated by Ottoman politicians and clerics under the pretext of their desire to dismantle the state, but they soon changed into a general anti-Christian pogrom as the killing moved to the Diyarbekir Vilayet and surrounding areas of Tur Abdin, which was inhabited by Assyrian/Syriac Christians. Contemporary accounts put the total number of Assyrians killed between 1894–96 at around 25,000.[1]

1843 and 1846 massacres in Hakkari

A series of massacres in Hakkari in the years 1843 and 1846 of Assyrians were carried out by the Kurdish emirs of Bohtan and Hakkari, Bedr Khan Bey and Nurullah. The massacres resulted in the killing of more than 10,000 Assyrians and the captivity of thousands of others.[1]

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/1843_and_1846_massacres_in_Hakkari

The İzmit Massacres

The İzmit massacres refer to atrocities committed in the region of İzmit, Turkey, during the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) which took place during the Greek Genocide. An Inter-Allied Commission of Enquiry that investigated the incidents, submitted a report, on 1 June 1921, about the events. In general it accepted the Greek claims that Turkish troops massacred more than 12,000 local civilians, while 2,500 were missing[1][2] and stated that the atrocities committed by the Turks in the Izmit peninsula “have been more considerable and ferocious than those on the part of the Greeks“.[1][4]

Ethnic cleansing policies undertaken by the Ottoman government were launched in various regions of the Ottoman Empire, including the Izmit region as early as 1915. This included the massive deportation of local Greek and Armenian communities.[1] In 1915, The New York Times reported that 19,000 Greeks from the Izmit province had been uprooted from their homes and driven to purely Turkish districts.[5] The Armenian Metropolitan of Izmit, Stephan Hovakimian stated, that, of the 80,000 Armenians belonging to his Diocese, 70,000 had been lost in exile, succumbing to hunger and exhaustion from long marches, and the slaughter of men and women upon arrival at their destination.[6] Later, in 1918, after the Armistice of Mudros a number of attacks by nationalist bands against the local Christian population were reported.

The Destruction of Psara 1824

Koutsodontis Nikolaos A.1800/1999

The Destruction of Psara on 20-22 June 1824, watercolour by the Primitive painter Nikolaos A. Koutsodontis. The continuous raids perpetrated by the inhabitants of Psara on the coasts of neighbouring Asia Minor were used by the Turks as grounds to ravage the island.

This was an event in which the Ottomans destroyed the civilian population of the Greek island of Psara on July 5, 1824.[1][2] According to George Finlay, the entire population of the island Psara before the massacre was about 7,000.[3] Since the massacre, the population of the island never rose over 1000.

The Batak massacre was a massacre of Bulgarians in Batak by Ottoman irregular troops in 1876

The number of victims ranges from 1,200 to 7,000, depending on the source.[1]

The role of Batak in the April Uprising was to take possession of the storehouses in the surrounding villages and to ensure that the insurgents would have provisions, also to block the main ways and keep the Turkish soldiers from receiving supplies. The task of Batak was to manage with the Pomak villages (Chepino and Korovo) should those try to prevent the uprising. Should the chetas in the nearby locations fail in their commands, the rest should have gathered in Batak. The only problem the organization of the uprising had expected was that Batak had to defend itself alone against the Turkish troops, but the risk was taken. After the April uprising started on 30 April 1876, part of the armed men in Batak, led by the voivode Petar Goranov, attacked the Turks.[2] They succeeded to eliminate part of the Ottoman leaders, but were reported to the authorities and 5,000 Bashi-bazouk were sent, mainly Pomaks (Slavic Muslims), led by Ahmet Aga from Barutin which surrounded the town.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9] At that time the Pomaks were a part of the Ottoman Muslim Millet. After a first battle, the men from Batak decided to negotiate with Ahmet Aga. He promised them the withdrawal of his troops under the condition that Batak disarmed. After the rebels had laid down their weapons, the Bashi-bazouk attacked them and beheaded them.[10]

While some of the leaders of the Revolutionary committee were surrendering the weapons, some managed to escape the village, but immediately after that all the territory was surrounded and no one else was let out. The Bashi-Bozouk went to the houses and raided them; many were burnt and they shot at everyone and everything. Many of the people decided to hide into the houses of the wealthy or in the church, which had a stronger construction and was going to protect them from the fire. On 2 May, those hidden in the House of Bogdan surrendered, because they were promised by Ahmet Aga to be spared. More than 200 men, women and children were led out, stripped out of their valuables and clothes, in order not to stain them with their blood, and were brutally killed. The Aga asked some of the wealthy men of Batak to go to his camp and lay down all the arms of the villagers. Amongst them was the mayor Trendafil Toshev Kerelov and his son, Petar Trandafilov Kerelov. They had reached an agreement that if the village were disarmed, the Pomaks would leave Batak for good. But instead, the Bulgarians were caught captive – once the arms were confiscated, all of them were beheaded, burnt alive or impaled. The murder of the leader Trendafil Kerelov was particularly violent and was described by a witness – his son’s wife Bosilka:

“My father in law went to meet the Bashi-Bаzouk when the village was surrounded by the men of Ahmet Aga, who said that he wanted all the arms laid down. Trendafil went to collect them from the villagers. When he surrendered the arms, they shot him with a gun and the bullet scratched his eye. Then I heard Ahmet Aga command with his own mouth for Trendafil to be impaled and burnt. The words he used were “Shishak aor” which is Turkish for “to put on a skewer” (as a shish kebab). After that, they took all the money he had, undressed him, gouged his eyes, pulled out his teeth and impaled him slowly on a stake, until it came out of his mouth. Then they roasted him while he was still alive. He lived for half-an-hour during this terrible scene. At the time, I was near Ahmet Aga with other Bulgarian women. We were surrounded by Bashi-Bozouk, who had us surrounded, and forced us to watch what was happening to Trendafil.”[11] One of her children, Vladimir, who was still a baby at his mother’s breast, was impaled on a sword in front of her eyes. “At the time this was happening, Ahmet Aga’s son took my child from my back and cut him to pieces, there in front of me. The burnt bones of Trendafil stood there for one month and only then they were buried”.[12]

The Candia massacre, 1898

The Candia massacre occurred on the island of Crete which was then part of the Ottoman Empire. It occurred as a reaction by armed Muslim irregular groups to the offer to the Christian community of a series of civil rights by foreign powers. They attacked the British security force in Candia (modern Heraklion), which was part of an international security force on the island. Muslim irregulars then proceeded to massacre the local Christians in the city. Fourteen British military personnel were murdered, the British vice-consul and his family were burnt alive in their house and 500–800 Christian inhabitants are estimated to have been massacred. A significant part of Candia was burnt and the massacre ended only after British warships began bombarding the city. The incident accelerated the end of Ottoman rule on Crete and two months later the last Ottoman soldier left the island.[1][2]

Massacre of Aleppo (1850)

The Aleppo Massacre was a riot perpetrated by Muslim residents of Aleppo against Christian residents.[1] The riot lasted for two days later in October 1850. The riot resulted in numerous deaths, including that of the Syriac Catholic Patriarch.

Third Siege of Missolonghi 1825-1826

The Third Siege of Missolonghi was fought in the Greek War of Independence, between the Ottoman Empire and the Greek rebels, from April 1825 to April 1826. The Ottomans had already tried and failed to capture the city in 1822 and 1823. They returned in 1825 with a stronger force of infantry and a stronger navy supporting the infantry. The Greeks held out for almost a year before they ran out of food and attempted a mass breakout, which however resulted in a disaster, with the larger part of the Greeks slain. This defeat was a key factor leading to intervention by the Great Powers who, hearing about the atrocities, felt sympathetic to the Greek cause.[3]

From April, 1825, to April 1826, this city of Missolonghi near Corinth in Greece was subjected to a pitiless siege by the Ottoman Empire. It was the third and most devastating seige. [1]

Sir Frederick Adam, the British governor of the nearby Ionian islands tried unsuccessfully to broker a deal. But the Turks slowly starved the Greeks inside the town.

An attempted sortie was betrayed. The seven thousand who attempted it were mostly slaughtered, or taken into slavery. Three thousand heads were displayed on the city walls as trophies.

The disaster was of such heart-rending scale, that it turned international opinion in favour of Greek independence. This was agreed in the London Protocol of 1830, and finally declared in 1832.

Attacks on Serbs during the Serbian–Ottoman War (1876–1878)

The events of persecution against the Serbian population occurred in Ottoman Kosovo in 1878, as a consequence of the Serbian–Ottoman War (1876–78).[1] Incoming Albanian refugees to Kosovo who were expelled by the Serb army from the Sanjak of Niș were involved in revenge attacks and hostile to the local Serb population.[2][3][4] Ottoman Albanian troops also participated in attacks, at the behest of Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II.[1]

With the Serbian capture of Niš, the Kumanovo villagers awaited the Serbian Army which went for Vranje and Kosovo.[11] The Serbian artillery fire was heard throughout the winter of 1877/78.[11] Ottoman Albanian troops from Debar and Tetovo fled the front and crossed the Pčinja, looting and raping along the way.[11]

On January 18, 1878, 17 armed Albanians descended from the mountains into Oslare, shouting while entering the village.[11] They first arrived at the house of Arsa Stojković, which they looted and emptied before his eyes, enraging Stojković who proceeded to punch one of them.[11] He was shot in the stomach and fell down, though still alive, he took a stake and delivered a mighty blow to the shooter’s head, dying with him.[11] The villagers then quickly entered an armed fight with the Albanians, killing them.[11]

On January 19, 1878, 40 Albanian deserters retreating from the Ottoman army broke into the house of elder Taško, a serf, in the Bujanovac region, tied up the males and raped his two daughters and two daughters-in-law,[12] then proceeded to loot the house and left the village.[11] Taško armed himself and persuaded the village to retaliate, tracing them in the snow and multiplying in numbers.[13] The Albanian deserters were dispersed, drunk, and were intercepted first at Lukarce, where six of them were beaten to death.[13] They killed all of them.[12]

With the taste of blood, revenge and victory, the retaliation grew into an uprising, with the avengers becoming rebels, riding armed on horse as soldiers, through the villages of Kumanovo and Kriva Palanka and called to revolt.[13] The movement was strengthened by Mladen Piljinski and his group’s killing of Ottoman Albanian haramibaşı Bajram Straž and his seven friends, whose severed heads were brought as trophies and used as flags in the villages. On January 20, 1878, the leaders of the Kumanovo Uprising were chosen.[13]

The Massacre of Serbs by the Ottomans 1901

The 1901 Massacres of Serbs were multiple massacres of Serbs in the Kosovo Vilayet of Ottoman Empire (modern-day Serbia, Kosovo and North Macedonia), carried out by Albanians.

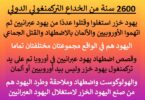

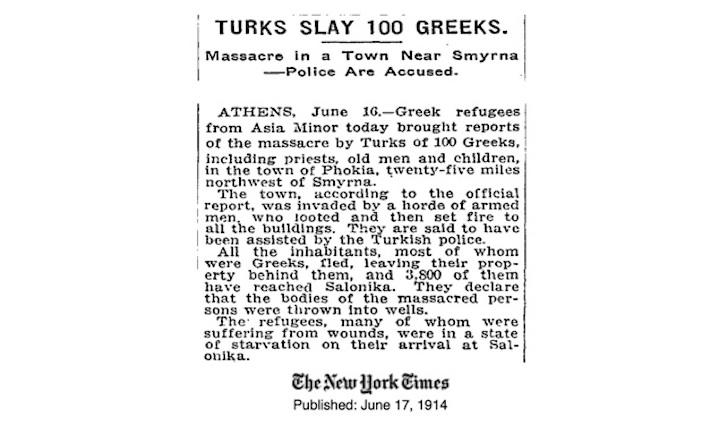

Massacre of Phocaea 1914

The pillage of Foça (Gr: Φώκαια or Phocaea) and the massacre of over 100 Greeks in June of 1914 was committed during the early phase of the Greek Genocide. While the death toll by direct killing was on a relatively light scale, the plan to force Greeks to flee was accomplished. The massacre and looting at Foça not only resulted in the mass expulsion of the Greeks from Phocaea, it also led to over 100,000 Greeks from the surrounding region abandoning their homes and seeking refuge in Greece and the neighboring islands.

The pillage and massacre at Foça was not an isolated incident. It was part of a wider policy to rid the Aegean coastline of Asia Minor of its vast Greek communities. The policy was put in place by the CUP (Committee for Union and Progress) political party as early as 1913 in the regions of Thrace and the Sea of Marmora and continued in the region around Smyrna in 1914, before the start of the First World War.

The location of the massacre was Eski Foça (Old Phocaea) situated some fifty kilometres north-west of Smyrna (Izmir). At the time, Eski Foça had a population of 8,000 Greeks and about 400 Turks.[1]

(1. George Horton, The Blight of Asia. Sterndale Classics UK, p 28.)

The massacre began on the night of the 12th of June when armed irregulars (Boshibozuks) who had earlier looted towns south of Menemen, attacked the town. The massacre lasted 24 hours. The eyewitness testimonies of Frenchmen Monsieurs Manciet and Sartiaux have provided the most detail in describing the sequence of events surrounding the massacre.

During the night, the organized bands continued the pillage of the town. At the break of dawn there was continual tres nourrie firing before the houses. Going out immediately, we four, we saw the most atrocious spectacle of which it is possible to dream. This horde, which had entered the town, was armed with Gras rifles and cavalry muskets. A house was in flames. From all directions the Christians were rushing to the quays seeking boats to get away in, but since the night there were none left. Cries of terror mingled with the sound of firing. The panic was so great that a woman with her child was drowned in sixty centimetres of water.2

Monsieur Manciet

Comment:

Mrs Elizabeth Ioannou Harkins:

My mother Vassilia Michaelidou was one of the children that was put on a ship along with her sister heading to safety to Egypt where they had relatives to take them in. Their parents were supposed to follow but did not make it as they were massacred by the Turks. It breaks my heart everyone I think about it.

Anfal Genocide

The Anfal genocide[3][4][5][6] was a genocide[7][8] that killed between 50,000[1] and 182,000[2] Kurds as well as several thousand Assyrians. It was committed during the ‘Al-Anfal campaign’ led by Ali Hassan al-Majid, on the orders of President Saddam Hussein, against Iraqi Kurdistan in northern Iraq during the final stages of the Iran–Iraq War.

The campaign’s name was taken from the title of Sura 8 (al-Anfal) in the Qur’an, which was used as a code name by the former Iraqi Ba’athist Government for a series of systematic attacks against the Kurdish fighters in northern Iraq between 1986 and 1989, with the peak in 1988. Sweden, Norway, South Korea and the United Kingdom officially recognize the Anfal campaign as a genocide.[9]

The genocide was part of the destruction of Kurdish villages which occurred during the Iraqi Arabization campaign.

Al-Anfal, the name used for the campaign, is the eighth sura (chapter) of the Qur’an. It explains the triumph of 313 followers of the Muslim faith over 900 pagans at the Battle of Badr in 624 AD. “Al Anfal” means ‘the spoils (of war)’ and was used to describe the military campaign of extermination and looting commanded by Ali Hassan al-Majid. His orders informed jash (literally “donkey’s foal” in Kurdish) units that taking cattle, sheep, goats, money, weapons and even Kurdish women was legal.[10]

One can see that the same could happen in Europe.

The Anfal campaign began in 1986, and lasted until 1989, and was headed by Ali Hassan al-Majid, a cousin of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein from Saddam’s hometown of Tikrit. The Anfal campaign included the use of ground offensives, aerial bombing, systematic destruction of settlements, mass deportation, firing squads, and chemical warfare, which earned al-Majid the nickname of “Chemical Ali“. The Iraqi Army was supported by Kurdish collaborators who were armed by the Iraqi government, so called Jash forces, who led the Iraqi troops to the Kurdish villages that often did not figure on maps as well as to their hideouts in the mountains. The Jash forces also promised the Kurdish population amnesties and gave their word of honor that a passage to flee was free, which both often turned out to be false.[11]

Be aware that this is what the Muslims are capable of if they get ascendency.

The Constantinople massacre of 1821

The Constantinople massacre of 1821 was orchestrated by the authorities of the Ottoman Empire against the Greek community of Constantinople in retaliation for the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence (1821–1830). As soon as the first news of the Greek uprising reached the Ottoman capital, there occurred mass executions, pogrom-type attacks,[1] destruction of churches, and looting of the properties of the city’s Greek population.[2][3] The events culminated with the hanging of the Ecumenical Patriarch, Gregory V and the beheading of the Grand Dragoman, Konstantinos Mourouzis.

Leading personalities of the Greek community, in particular the Ecumenical Patriarch, Gregory V, and the Grand Dragoman, Konstantinos Mourouzis, were accused of having knowledge of the revolt by the Sultan, Mahmud II, but both pleaded innocence. Nevertheless, the Sultan requested a fatwa allowing a general massacre against all Greeks living in the Empire[8] from the Shaykh al-Islām, Haci Halil Efendi. The Shaykh obliged, however the Patriarch managed to convince him that only a few Greeks were involved in the uprising, and the Shaykh recalled the fatwa.[4] Haci Halil Efendi was later exiled and executed by the Sultan for this.[7]

The Ecumenical Patriarch was forced by the Ottoman authorities to excommunicate the revolutionaries, which he did on Palm Sunday, April, 15 [O.S. April, 3] 1821. Although he was unrelated to the insurgents, the Ottoman authorities still considered him guilty of treason because he was unable, as representative of the Orthodox population of the Ottoman Empire, to prevent the uprising.[9]

The Adana massacre of 1909

The Adana massacre occurred in the Adana Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire in April 1909. A massacre of Armenian Christians by Ottoman Muslims in the city of Adana amidst the Ottoman countercoup of 1909 expanded to a series of anti-Armenian pogroms throughout the province.[2] Reports estimated that the Adana Province massacres resulted in the deaths of as many as 20,000–30,000 Armenians.[3][4]

In 1908, the Young Turk government came to power in a bloodless revolution. Within a year, the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian population, empowered by the dismissal of Abdul Hamid II, began organizing politically in support of the new government, which promised to place them on equal legal footing with their Muslim counterparts.[8]

Having long endured so-called dhimmi status, and having suffered the brutality and oppression of Hamidian leadership since 1876, the Armenians in Cilicia perceived the nascent Young Turk government as a godsend. With Christians now being granted the right to arm themselves and form politically significant groups, it was not long before Abdul Hamid loyalists, themselves acculturated into the system that had perpetrated the Hamidian massacres of the 1890s, came to view the empowerment of the Christians as coming at their expense.

The Hamidian massacres (Armenian Massacres) of 1894–1896

These were massacres of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire that took place in the mid-1890s. It was estimated casualties ranged from 80,000 to 300,000,[3] resulting in 50,000 orphaned children.[4] The massacres are named after Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who, in his efforts to maintain the imperial domain of the collapsing Ottoman Empire, reasserted Pan-Islamism as a state ideology.[5] Although the massacres were aimed mainly at the Armenians, they turned into indiscriminate anti-Christian pogroms in some cases, such as the Diyarbekir massacre, where, at least according to one contemporary source, up to 25,000 Assyrians were also killed.[6]

The origins of the hostility toward Armenians lay in the increasingly precarious position in which the Ottoman Empire found itself in the last quarter of the 19th century. The end of Ottoman dominion over the Balkans was ushered in by an era of European nationalism and an insistence on self-determination by many territories long held under Ottoman rule. The Armenians of the empire, who were long considered second-class citizens, had begun in the mid-1860s and early 1870s to ask for civil reforms and better treatment from government. They pressed for an end to the usurpation of land, “the looting and murder in Armenian towns by Kurds and Circassians, improprieties during tax collection, criminal behavior by government officials and the refusal to accept Christians as witnesses in trial.”[8] These requests went unheeded by the central government. When a nascent form of nationalism spread among the Armenians of Anatolia, including demands for equal rights and a push for autonomy, the Ottoman leadership believed that the empire’s Islamic character and even its very existence were threatened.

The sultan, however, was not prepared to relinquish any power. Abdul Hamid believed that the woes of the Ottoman Empire stemmed from “the endless persecutions and hostilities of the Christian world.”[9] He perceived the Ottoman Armenians to be an extension of foreign hostility, a means by which Europe could “get at our most vital places and tear out our very guts.”[10] Turkish historian and Abdul Hamid biographer Osman Nuri observed, “The mere mention of the word ‘reform’ irritated him [Abdul Hamid], inciting his criminal instincts.”[11] Upon hearing of the Armenian delegation’s visit to Berlin in 1878, he bitterly remarked, “Such great impudence…Such great treachery toward religion and state…May they be cursed upon by God.”[12] While he admitted that some of their complaints were well-founded, he likened the Armenians to “hired female mourners [pleureuses] who simulate a pain they do not feel; they are an effeminate and cowardly people who hide behind the clothes of the great powers and raise an outcry for the smallest of causes.”[13]

In 1894, the sultan began to target the Armenian people in a precursor to the Hamidian massacres. This persecution strengthened nationalistic sentiment among Armenians. The first notable battle in the Armenian resistance took place in Sasun. Hunchak activists encouraged resistance against double taxation and Ottoman persecution. The ‘Armanian Revolutionary Federation’ armed the people of the region. The Armenians confronted the Ottoman army and Kurdish irregulars at Sasun, finally succumbing to superior numbers and to Turkish assurances of amnesty (which was never granted).[19]

In response to the resistance at Sasun, the governor of Mush responded by inciting the local Muslims against the Armenians. Historian Patrick Balfour, 3rd Baron Kinross writes that massacres of this kind were often achieved by gathering Muslims in a local mosque and claiming that the Armenians had the aim of “striking at Islam.”[20] Sultan Abdul Hamid sent the Ottoman army into the area and also armed groups of Kurdish irregulars. The violence spread and affected most of the Armenian towns in the Ottoman Empire.[21]

“Turkey and the Armenian Atrocities” by Rev. Edwin M. Bliss, Edgewood Publishing Company, 1896, p. 432

The worst atrocity took place in Urfa, where Ottoman troops burned the Armenian cathedral, in which 3,000 Armenians had taken refuge, and shot at anyone who tried to escape.[26]

Abdul Hamid’s private first secretary wrote in his memoirs about Abdul Hamid that he “decided to pursue a policy of severity and terror against the Armenians, and in order to succeed in this respect he elected the method of dealing them an economic blow… he ordered that they absolutely avoid negotiating or discussing anything with the Armenians and that they inflict upon them a decisive strike to settle scores.”[27]

The killings continued until 1897. In that last year, Sultan Hamid declared the Armenian Question closed. Many Armenian revolutionaries had either been killed or escaped to Russia. The Ottoman government closed Armenian societies and restricted Armenian political movements.

The Siege of Tripolitsa (The Fall of Tripolitsa) 1821

The Siege of Tripolitsa or the Fall of Tripolitsa to revolutionary Greek forces in the summer of 1821 marked an early victory in the Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire, which had begun earlier in that year.

Situated in the middle of Peloponnese, Tripolitsa was an important town in southern Greece, as well as the administrative centre for Ottoman rule. This made it a target for the Greek revolutionaries. Many rich Turks and Jews lived there, together with Ottoman refugees escaping massacres in the country’s southern districts.[2][10]

It was also a potent symbol for revenge. Its Greek population had been massacred by the Ottoman forces in the past. The de facto commander in chief of the Greek forces, Theodoros Kolokotronis, now focused on the capital of the province. He set up fortified camps in the surrounding places, establishing several headquarters in the nearby villages.[14]

In the three days following the capture of the city, Muslims (Turks and other Muslims) alongside Jewish and Christians supporters of the Ottoman regime, inhabitants of Tripolitsa, were exterminated.[2][3]

Describing the massacres that occurred following the capture of Tripolitsa, historian W. Alison Phillips noted that:

For three days the miserable inhabitants were given over to lust and cruelty of a mob of savages. Neither sex nor age was spared. Women and children were tortured before being put to death. So great was the slaughter that Kolokotronis himself says that, from the gate to the citadel his horse’s hoofs never touched the ground. His path of triumph was carpeted with corpses. At the end of two days, the wretched remnant of the Mussulmans were deliberately collected, to the number of some two thousand souls, of every age and sex, but principally women and children, were led out to a ravine in the neighboring mountains and there butchered like cattle.[23]

Kolokotronis says in his memoirs:[24]

Inside the town they had begun to massacre. … I rushed to the palace … If you wish to hurt these Albanians, I cried, “kill me rather; for, while I am a living man, whoever first makes the attempt, him will I kill the first.” … I was faithful to my word of honor … Tripolitsa was three miles in circumference. The [Greek] host which entered it, cut down and were slaying men, women, and children from Friday till Sunday. Thirty-two thousand were reported to have been slain. One Hydriote [boasted that he had] killed ninety. About a hundred Greeks were killed; but the end came [thus]: a proclamation was issued that the slaughter must cease. … When I entered Tripolitsa, they showed me a plane tree in the market-place where the Greeks had always been hung. I sighed. “Alas!” I said, “how many of my own clan — of my own race — have been hung there!” And I ordered it to be cut down. I felt some consolation then from the slaughter of the Turks. … [Before the fall] we had formed a plan of proposing to the Turks that they should deliver Tripolitsa into our hands, and that we should, in that case, send persons into it to gather the spoils together, which were then to be apportioned and divided among the different districts for the benefit of the nation; but who would listen?

There were about one hundred foreign officers present[citation needed] at the scenes of atrocities and looting committed in Tripolitsa, Friday to Sunday. Based upon eyewitness accounts and descriptions provided by these officers, William St. Clair wrote:

Upwards of ten thousand Turks were put to death. Prisoners who were suspected of having concealed their money were tortured. Their arms and legs were cut off and they were slowly roasted over fires. Pregnant women were cut open, their heads cut off, and dogs’ heads stuck between their legs. From Friday to Sunday the air was filled with the sound of screams… One Greek boasted that he personally killed ninety people. The Jewish colony was systematically tortured… For weeks afterwards starving Turkish children running helplessly about the ruins were being cut down and shot at by exultant Greeks… The wells were poisoned by the bodies that had been thrown in…[16]

The Turks of Greece left few traces. They disappeared suddenly and finally in the spring of 1821 unmourned and unnoticed by the rest of the world….It was hard to believe then that Greece once contained a large population of Turkish descent, living in small communities all over the country, prosperous farmers, merchants, and officials, whose families had known no other home for hundreds of years…They were killed deliberately, without qualm or scruple, and there was no regrets either then or later.[25]

The massacre at Tripolitsa was the final and largest in a series of massacres against Muslims in the region during the early months of the revolt. Upwards of twenty thousand Muslim men, women and children were killed during this time, often with the support of the local clergy.[26][27][28]

The Simele Massacre of 1933.

The Simele massacre was a massacre committed by the armed forces of the Kingdom of Iraq led by Bakr Sidqi during a campaign targeting the Assyrians of northern Iraq in 1933. The term is used to describe not only the massacre in Simele, but also the killing spree that took place among sixty-three Assyrian villages in the Dohuk and Mosul districts that led to the death of as many as 6,000 Assyrians.[1][2]

The Kasos Massacre 1824

The Kasos massacre was the massacre of Greek civilians during the Greek War of Independence by Ottoman forces after the Greek Christian population rebelled against the Ottoman Empire.

The Turks and Egyptians ravaged several Greek islands during the Greek Revolution, including those of Chios, Kos, Rhodes, Kasos and Psara. The Chios Massacre of 1822 became one of the most notorious occurrences of the war. Mehmet Ali, the Pasha of Egypt, dispatched his naval fleet to Kasos and on May 27, 1824 killed the population.

Another crime and genocide of Greeks by the Turkish Ottomans.

Massacres of Jews

According to the Jewish Virtual Library, Jewish populations in the Peloponnese had become in disfavour with the Greeks by apparently supporting the Ottomans, and during the Greek War of Independence thousands of Jews were massacred alongside the Ottoman Turks by the Greek rebels, with the Jewish communities of Mistras, Tripolis, Kalamata and Patras completely destroyed. A few survivors moved north to areas still under Ottoman rule.[46] St. Clair notes that some amongst the clergy incited murder of Jewish populations as they had of Turkish ones.[47]

Steven Bowman claims that despite the fact that many Jews were killed, they were not targeted specifically: “Such a tragedy seems to be more a side-effect of the butchering of the Turks of Tripolis, the last Ottoman stronghold in the South where the Jews had taken refuge from the fighting, than a specific action against Jews per se.“[48] However, in the case of Vrachori[9] a massacre of a Jewish population occurred first, and the Jewish population in the Peloponnese regardless was effectively decimated, unlike that of the considerable Jewish populations of the Aegean, Epirus and other areas of Greece in the several following conflicts between Greeks and the Ottomans later in the century. Many Jews within Greece and throughout Europe were however supporters of the Greek revolt, using their wealth (as in the case of the Rothschilds) as well as their political and public influence to assist the Greek cause. Following the state’s establishment, it also then attracted many Jewish immigrants from the Ottoman Empire, as one of the first states in the world to grant legal equality to Jews.[49]

Prisoners of War

Both sides routinely slaughtered prisoners of war, despite guarantees. The Turks would typically offer captured Greeks the option of conversion to Islam or death. Greeks often chose death because they were deeply attached to their religion. Turkish prisoners of war were typically at the mercy of the commanders that captured them. There exists examples of massacres of prisoners after they were promised guarantees of safety, such as the garrison of Kalamata. Yet, there was remarkably humane treatment such as the Turkish garrison of the Acropolis of Athens which was saved by Karaiskakis.

The Assyrian Genocide between 1914 and 1920

The Assyrian genocide was the mass slaughter of the Assyrian population of the Ottoman Empire and those in neighbouring Persia by Ottoman troops[1][2] during the First World War, in conjunction with the Armenian and Greek genocides.[4][5]

The Assyrian civilian population of upper Mesopotamia (the Tur Abdin region, the Hakkâri, Van, and Siirt provinces of present-day southeastern Turkey, and the Urmia region of northwestern Iran) was forcibly relocated and massacred by the Ottoman army, together with other armed and allied Muslim peoples, including Kurds and Circassians, between 1914 and 1920, with further attacks on unarmed fleeing civilians conducted by local Arab militias.[4]

Unlike the Armenians, there were no orders to deport Assyrians. The attacks against them were not of a standardized nature and incorporated various methods; in some cities, all Assyrian men were slain and the women were forced to flee. These massacres were often carried out upon the initiatives of local politicians and Kurdish tribes. Exposure, disease and starvation during the flight of Assyrians increased the death toll, and women were subjected to widespread sexual abuse in some areas.

A figure of 275,000 deaths was been reported. It should be noted that the Hamidiye had received assurances from the Ottoman Sultan that they could kill Assyrians and Armenians with impunity.[4] This is the problem when Muslims gain ascendency.

The Ottoman Empire began massacring Assyrians in the nineteenth century, a time of friendly relations between the Ottomans and the British, who were defending the Ottomans from the Russian Empire’s efforts to include under its protection the communities of Ottoman Orthodox Christians.[4] In October 1914, the Ottoman Empire began deporting and massacring Assyrians and Armenians in Van.[4] After attacking Russian cities and declaring war on Britain and France, the Empire declared a holy war on Christians.[4] The German Kaiser and the German Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire directed and orchestrated the holy war, and financed the Ottomans’ war against the Russian Empire.[4]

The Great Famine of Mount Lebanon (1915–1918)

The Great Famine of Mount Lebanon (1915–1918) was a period of mass starvation during World War I that resulted in 200,000 deaths.[1]

Allied forces blockaded the Eastern Mediterranean, as they had done with the German Empire in Europe, in order to stranglehold the economy. They did so knowing that it might lead to an impact on civilians in the region.[2] The situation was made worse by Jamal Pasha, commander of the Fourth Army of the Ottoman Empire, who barred crops from Syria from entering Mount Lebanon.[3] Unfortunately, a swarm of locusts devoured the remaining crops.[4][3] This created a famine that led to the deaths of half of the population of the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, a semi-autonomous subdivision of the Ottoman Empire and the precursor of modern-day Lebanon.

About 200,000 people starved to death at a time when the population of Mount Lebanon was around 400,000 people.[4][12] This Mount Lebanon famine caused the highest fatality rate by population during World War I.[3] Bodies were piled in the streets. People were reported to be eating street animals. Some people were said to have resorted to cannibalism.[3][4]

Spain under Muslim Rule

Under Muslim rule, Jews and Christians in Spain were reduced to ‘dhimmi’ status forced to pay a special tax and often subject to pogroms and persecution. The much vaunted tolerance is mythical. The general population were subject to rigid control by Muslim clerics. [The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise by Dario Fernandez-Morera.] The Muslims in Spain were colonial occupiers who called the territory “Al-Andalus” and imposed Arabic as the official language. Islam arrived in that region with the arrival of the Moors during the 8 th century AD, and subjugated almost the entire peninsula in less than a decade. The rule of the Moors in Spain lasted until 1492, when the last surviving Muslim state in the Iberian Peninsula, the Emirate of Granada, was conquered by the Christians.

With regards to the sources from the time of the Umayyad invasion, no Muslim accounts are available, whereas the only Christian source, the so-called Chronicle of 754 , is rather vague about the events that occurred. A 9 th century AD Muslim account, written by the historian Ibn Abd al-Hakam, provides a rather interesting story regarding the cause of the Umayyad invasion.

According to Ibn Abd al-Hakam, a Visigothic nobleman by the name of Count Julian had approached Tariq ibn Ziyad, an Umayyad commander for his help. One of the count’s daughters had been raped by Roderic, the Visigothic king. Since the count could do nothing to punish the king for his crime, he decided to invite the Umayyads to invade the kingdom. Therefore, Julian provided ships to carry the Umayyad army across the Strait of Gibraltar.

Since Ibn Abd al-Hakam was writing more than a century after the Umayyad invasion of the Iberian Peninsula, it is quite likely that facts and legends were mixed up. It has been suggested that the story of Count Julian’s grudge against Roderic belongs to the latter. There are other legends about the Umayyad invasion as well. One of these alleges that the invaders received help from ‘Jews’ living in the Visigothic Kingdom. In return for less restrictions under the Muslims, the Jews of certain Christian cities agreed to open the gates for them. This story has been used by Christians later on to blame the Jews for collaborating with the Muslims.

The mid-11th Century saw any tolerance of diversity disapear as the Iberian peninsula was squabbled over by increasingly strict, small kingdoms. Many Christians and Jews were forced either to convert, emigrate, or be killed. The distinguished historian Bernard Lewis wrote that the status of non-Muslims in Islamic Spain was a sort of second-class citizenship [44]. Bernard Lewis writes:

Second-class citizenship, though second class, is a kind of citizenship. It involves some rights, though not all, and is surely better than no rights at all…

…A recognized status, albeit one of inferiority to the dominant group, which is established by law, recognized by tradition, and confirmed by popular assent, is not to be despised.

Bernard Lewis, The Jews of Islam, 1984

Jews and Christians did retain some freedom under Muslim rule, providing they obeyed certain rules. Although these rules would now be considered unacceptable.

- they were not forced to live in ghettoes or other special locations

- they were not slaves

- they were not prevented from following their faith

- they were not forced to convert or die under Muslim rule

- they were not banned from any particular ways of earning a living; they often took on jobs shunned by Muslims;

- these included unpleasant work such as tanning and butchery

- but also pleasant jobs such as banking and dealing in gold and silver

- they could work in the civil service of the Islamic rulers

- Jews and Christians were able to contribute to society and culture

More realistically is that Jews and Christians were severely restricted in Muslim Spain, by being forced to live in a state of ‘dhimmitude’. (A dhimmi is a non-Muslim living in an Islamic state who is not a slave, but does not have the same rights as a Muslim living in the same state.) In Islamic Spain, Jews and Christians were tolerated if they:

- acknowledged Islamic superiority

- accepted Islamic power

- paid a tax called Jizya to the Muslim rulers and sometimes paid higher rates of other taxes

- avoided blasphemy

- did not try to convert Muslims

- complied with the rules laid down by the authorities. These included:

- restrictions on clothing and the need to wear a special badge

- restrictions on building synagogues and churches

- not allowed to carry weapons

- could not receive an inheritance from a Muslim

- could not bequeath anything to a Muslim

- could not own a Muslim slave

- a dhimmi man could not marry a Muslim woman (but the reverse was acceptable)

- a dhimmi could not give evidence in an Islamic court

- dhimmis would get lower compensation than Muslims for the same injury

At times there were restrictions on practicing one’s faith too obviously. Bell-ringing or chanting too loudly were frowned on and public processions were restricted.

The Muslim rulers didn’t give their non-Muslim subjects equal status; as Bat Ye’or has stated, the non-Muslims came definitely at the bottom of society.

The position of non-Muslims in Spain deteriorated substantially from the middle of the 11th century as the rulers became more strict and Islam came under greater pressure from outside.

References:

Peacock, Herbert Leonard, A History of Modern Europe, (Heinemann Educational Publishers; 7th edition edition, September 1982) p. 219-220

William St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free – The Philhellenes in the War of Independence, Oxford University Press London 1972 p.2 ISBN 0192151940

Fisher, H.A.L, A History of Europe, (Edward Arnold, London, 1936 & 1965) p. 881-882

W. Alison Phillips, The War of Greek Independence, 1821 to 1833, London, 1897, p. 48

William St. Clair, That Greece Might Still Be Free – The Philhellenes in the War of Independence

George Finlay, History of the Greek Revolution and the Reign of King Otho, edited by H. F. Tozer, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1877 Reprint London 1971