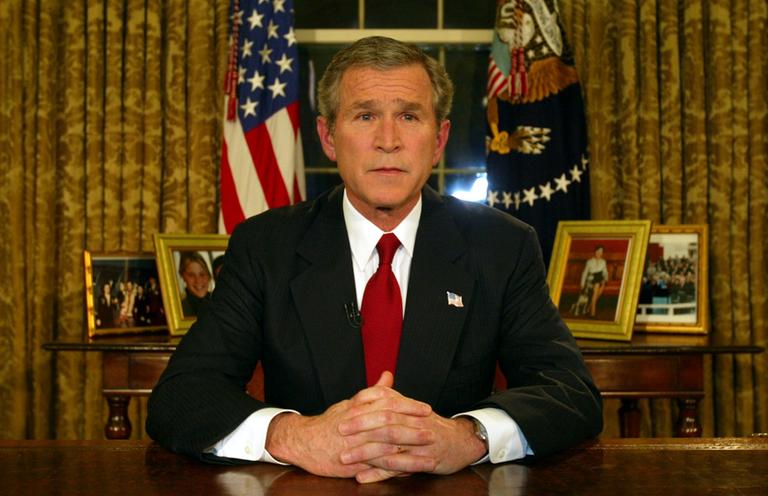

The fact that Bush administration officials used false and distorted evidence to justify their invasion of Iraq makes their decision all the more deplorable. But in the end, it doesn’t matter whether or not Saddam Hussein had warehouses full of WMDs, the war in Iraq would still have been a crime against peace and a violation of the laws and customs of war. And Bush and his war council could still be charged as war criminals.

As early as September 2004, then-UN Secretary General Kofi Annan told the BBC that the invasion and occupation of Iraq was a war “not in conformity with the UN charter from our point of view.” In fact, he acknowledged, “From the charter point of view, it was illegal.” Annan was referring to Article 2 of the UN charter, which states in part, “All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.” Article 51 of the UN charter does guarantee a nation’s right to self-defense “if an armed attack occurs.” Article 51 says nothing about preemptive self-defense absent an armed attack. However, preemptive self-defense is a principle that has long been recognized in international law. A nation need not wait until it is actually attacked, but the certainty that an attack is coming must be “instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means,” as then Secretary of State Daniel Webster wrote to the British government in 1837. (In the course of putting down a rebellion in Canada, the British had claimed self-defense when they captured and burned an American ship they suspected of being involved in gun running for the Canadians.) Webster’s insistence that a threat be “instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means” remains the de facto standard for legitimate preemptive self-defense.

In March 2003, it simply was not the case that the United States faced a danger that was “instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means” even if Iraq were in possession of the weapons the Bush administration claimed it had. On the other hand, during that spring there certainly was one nation facing a determined, powerful, even nuclear-armed enemy a nation threatened with the “instant, overwhelming” danger of attack. But it wasn’t the United States or one of its allies. It was Iraq. Given that the United States made no secret of its intentions or its military preparations, would Iraq have been justified in attacking the United States?

The view that preemptive self-defense is only legitimate in extremis is at odds with a September 2002 Bush administration document titled “The National Security Strategy of the United States,” which is often described as the best official formulation of the so-called Bush Doctrine. Arguing that the “security environment confronting the United States today is radically different from what we have faced before,” the document outlined a new strategy in which the government’s “first duty” is as always “to protect the American people and American interests.” Therefore, the United States has long maintained the option of preemptive actions to counter a sufficient threat to our national security. The greater the threat, the greater is the risk of inaction and the more compelling the case for taking anticipatory action to defend ourselves, even if uncertainty remains as to the time and place of the enemy’s attack. To forestall or prevent such hostile acts by our adversaries, the United States will, if necessary, act preemptively. In his memoir, Decision Points, Bush describes the elaboration of his “doctrine” this way: After 9/11, I developed a strategy to protect the country that came to be known as the Bush Doctrine: First, make no distinction between the terrorists and the nations that harbor them and hold both to account. Second, take the fight to the enemy overseas before they can attack us again here at home. Third, confront threats before they fully materialize. And fourth, advance liberty and hope as an alternative to the enemy’s ideology of repression and fear.

The doctrine that there is “no distinction” between terrorists and the country where they are located underlay the argument for the war against Afghanistan, and the administration intended to apply the same doctrine to its attack on Iraq.

That is why they were quite willing to use torture to extract statements from detainees “proving” that Saddam Hussein had conspired with al Qaeda.

In fact, Bush officials were prepared to deploy a number of arguments for the war. The problem they had, as Paul Wolfowitz later told Vanity Fair, was deciding which argument would be most effective. “The truth is,” he said, “that for reasons that have a lot to do with the US government bureaucracy, we settled on the one issue that everyone could agree on, which was weapons of mass destruction as the core reason.” This is a rather startling statement, which Wolfowitz attempted to clarify, explaining that “there have always been three fundamental concerns. One is weapons of mass destruction, the second is support for terrorism, the third is the criminal treatment of the Iraqi people.”

The third issue, he said was “a reason to help the Iraqis but … not a reason to put American kids’ lives at risk.” (Or presumably, the lives of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis.) “That second issue about links to terrorism is the one about which there’s the most disagreement within the bureaucracy,” Wolfowitz continued. So that left the Bush administration with only the weapons of mass destruction as a pretext for war.

So the Bush administration began telling the US public and the world that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons that could kill thousands, and that his government represented “a direct and growing threat” to the United States.

Neither of these things was true. Iraq posed no direct and imminent threat to the United States. Therefore, the US invasion of Iraq was, as Kofi Annan stated, illegal. But didn’t the UN Security Council tacitly approve military action against Iraq when it passed Security Council Resolution 1441? This was last of several resolutions requiring Iraq to comply with weapons inspections by the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Some proponents of the Iraq War have made that argument. However, the US ambassador to the United Nations at the time, John Negroponte, sought to dispel exactly those fears that the United States would interpret the resolution as a license for war. In the discussions before the vote, Negroponte assured the Security Council, “This resolution contains no ‘hidden triggers’ and no ‘automaticity’ with respect to the use of force. If there is a further Iraqi breach, reported to the Council by UNMOVIC, the IAEA or a Member State, the matter will return to the Council for discussions.” The British ambassador used almost identical words to reassure the Security Council that before attacking Iraq, the United States and Britain would seek the Security Council’s blessing.

That is not what happened, however. On February 24, 2003, Washington and London did bring a resolution for war to the Security Council, but it became apparent that two permanent members, France and Russia, would veto it if it came to a vote. Meeting with British Prime Minister Tony Blair and the presidents of Spain and Portugal, Bush decided to withdraw the resolution. “We all agreed,” he wrote in his memoir, that “the diplomatic track had reached its end.”

Source: https://vk.com/public195259598