THE

INFLUENCE OF BUDDHISM

ON

PRIMITIVE CHRISTIANITY

by

Arthur Lillie

AUTHOR OF “BUDDHISM IN CHRISTENDOM,” ETC.

LONDON

SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO.

NEW YORK: CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1893

Preface.

A volume that proves that much of the New Testament is parable rather than history will shock many readers, but from the days of Origen and Clement of Alexandria to the days of Swedenborg the same thing has been affirmed. The proof that this parabolic writing has been derived from a previous religion will shock many more. The biographer of Christ has one sole duty, namely, to produce the actual historical Jesus. In the New Testament there are two Christs, an Essene and an anti-Essene Christ, and all modern biographers who have sought to combine the two have failed necessarily. It is the contention of this work that Christ was an Essene monk; that Christianity was Essenism; and that Essenism was due, as Dean Mansel contended, to the Buddhist missionaries “who visited Egypt within two generations of the time of Alexander the Great.” (“Gnostic Heresies,” p. 31.)

The Reformation, in the view of Macaulay, was the struggle of layman versus monk. In consequence, many good Protestants are shocked to hear such a term applied to the founder of their creed. But here I must point out one fact. In the Essene monasteries, as in the Buddhist, there was no life vow. This made the monastery less a career than a school for spiritual initiation. In modern monasteries St. John of the Cross can dream sweet dreams of God in one cell, and his neighbour may be Friar Tuck, but to both the monastery is a prison. This alters the complexion of the celibacy question, and so does the fact that the Christians were fighting a mighty battle with the priesthoods.

The Son of Man envied the security of the crannies of the “fox.” He called his opponents “wolves.” His flock after his death met with closed doors for fear of the Jews. The “pure gospel,” says the Clementine Homilies (ch. ii. 17), was “sent abroad secretly” after the removal to Pella. The new sect, not as Christians but as Essenes, were tortured, killed, hunted down. To such, “two coats,” “wives,” daily wine celebrations were scarcely fitted.

Twice has Buddhism invaded the West, once at the birth of Christianity, and once when the Templars brought home from Palestine Cabbalism, Sufism, Freemasonry. And our zealous missionaries in Ceylon and elsewhere, by actively translating Buddhist books to refute them, have produced a result which is a little startling. Once more Buddhism is advancing with giant strides. Germany, America, England are overrun with it. M. Léon de Rosny, a professor of the Sorbonne, announces that in Paris there are 30,000 Buddhists at least. A French frigate came back from China the other day with one-third of the crew converted Buddhists. Schopenhauer admits that he got the philosophy which now floods Germany from a perusal of English translations of Buddhist books. Even the nonsense of Madame Blavatsky has a little genuine Buddhism at the bottom, which gives it a brief life.

The religions of earth mean strife and partisan watch-cries, partisan symbols, partisan gestures, partisan clothes. But as the daring climber mounts the cool steep, the anathemas of priests fall faintly on the ear, and the largest cathedrals grow dim, in a pure region where Wesley and Fenelon, Mirza the Sufi and Swedenborg, Spinoza and Amiel, can shake hands. If this new study of Buddhism has shown that the two great Teachers of the world taught much the same doctrine, we have distinctly a gain and not a loss. That religion was the religion of the individual, as discriminated from religion by body corporate.

Contents.

Influence of Buddhism on Christianity

Introductory.

In the Revue des Deux Mondes, July 15th, 1888, M. Émile Burnouf has an article entitled “Le Bouddhisme en Occident.”

M. Burnouf holds that the Christianity of the Council of Nice was due to a conflict between the Aryan and the Semite, between Buddhism and Mosaism:—

“History and comparative mythology are teaching every day more plainly that creeds grow slowly up. None come into the world ready-made, and as if by magic. The origin of events is lost in the infinite. A great Indian poet has said, ‘The beginning of things evades us; their end evades us also. We see only the middle.'”

M. Burnouf asserts that the Indian origin of Christianity is no longer contested: “It has been placed in full light by the researches of scholars, and notably English scholars, and by the publication of the original texts…. In point of fact, for a long time, folks had been struck with the resemblances, or rather the identical elements contained in Christianity, and Buddhism. Writers of the firmest faith and most sincere piety have admitted them. In the last century these analogies were set down to the Nestorians, but since then the science of Oriental chronology has come into being, and proved that Buddha is many years anterior to Nestorius and Jesus. Thus the Nestorian theory had to be given up. But a thing may be posterior to another without proving derivation. So the problem remained unsolved until recently, when the pathway that Buddhism followed was traced, step by step, from India to Jerusalem.”

What are the facts upon which scholars abroad are basing the conclusions here announced? I have been asked by the present publishers to give a short and popular answer to this question. The theory of this book, stated in a few words, is that at the date of King Asoka (B.C. 260), Persia, Greece, Egypt, Palestine had been powerfully influenced by Buddhist propagandism.

Buddha, as we know from the Rupnath Rock inscription, died 470 years before Christ. He announced before he died that his Dharma would endure five hundred years. (Oldenburg, “Buddhism,” p. 327.) He announced also that his successor would be Maitreya, the Buddha of “Brotherly Love.” In consequence, at the date of the Christian era, many lands were on the tip-toe of expectation. “According to the prophecy of Zoradascht,” says the First Gospel of the Infancy, “the wise men came to Palestine,” expecting, probably, Craosha, as the Jews expected Messiah. The time passed. Jesus was executed. His followers dispersed in consternation. The conception that he was the real Messiah was apparently long in taking definite form.

First came a book of “sayings” only. Then a gospel was constructed—the Gospel of the Hebrews—of which only a small fragment can be restored. This was the basis of many other gospels. At the date of Irenæus (180 A.D.) they were very numerous. (Hœr i. 19.) As only the Old Testament, at that time, was considered the Bible, the composers of these gospels apparently thought it no great sin to draw on the Alexandrine library of Buddhist books for much of their matter, it being a maxim of both the Essenes and the early Christians that a holy book was more allegory than history.

But before I compare the Buddhist and Christian narratives, I must say a word about the early religion of the Jews.

Chapter 1.

Moses.

Until within the last forty years the Old Testament has been practically a sealed book.

It found interpreters, no doubt — two great groups.

The first group pointed to its useless and arbitrary edicts, and pronounced them the inventions of priests inspired by fraud and greed.

The second group practically admitted the arbitrary and useless nature of most of the edicts, but maintained that they were given by the All-wise, in a book penned by His finger, to miraculously prepare a nation distinct from the other nations of the earth, for a special purpose. They were “types” of a higher revelation, a “better covenant.”

Practically, with both of these interpreters Mosaism was a pure comedy.

But comparative mythology, unborn yesterday, is telling a different story. It shows that the religion of the Jews, far from having been a distinct religion miraculously given to a peculiar people, had the same rites and gods as the creeds of its Semitic neighbours. It shows us these Semites, or descendants of Shem, in two great groups, differing much in language and religion. It shows us the southern Semites, the Arabs, the Himyarites, the Ethiopians. It shows us the northern group, the Babylonians or Chaldeans, the Assyrians, the Arameans, the Canaanites, the Hebrews. It shows us their gods, El and Yahve, and Astarte of Sidon; and going a step back shows how the Semites borrowed from an earlier civilisation, that of the Acadians, the yellow-faced Mongols who seem to have preceded the white races everywhere. “The Semite borrowed the old Acadian pantheon en bloc,” says Professor Sayce (“Ancient Empires,” p. 151).

But the work of the archæologist and the anthropologist has been still more important.

The former has suddenly revealed to us chapters in the history of human experience hitherto undreamt of. He has allowed us to peer far, far into the past, to see man at an incalculable distance.

Thousands and thousands of years before Cain and Abel we see the palæolithic man, “dolichocephalic and with prominent jaws,” pursue the great migrations of urus, reindeer, mammoth, and the thick-nose rhinoceros from Cumberland to Algeria, and Algeria to Cumberland, passing dry-shod to France, and from Sicily to Africa. He is naked. He is armed with a javelin with a flint head. He is an animal, struggling for survival with other animals. He eats his foes as wolves eat vanquished wolves. To extract the marrow from their bones he cracks them with his poor flint “celt” or “langue du chat;” and these cracked human bones 240,000 years afterwards are found in caves and in beds of gravel and sand, and brick earth, and tell their story. Some are charred, which proves that the notion of sacrifice to an unseen being was due to him.

To this poor savage our debt is quite incalculable.

- He invented the missile. This made the monkey dominant in the animal world. He became a man.

- He invented religion.

Here the valuable work of the anthropologist chimes in. He has collected the records of ancient and modern savages, and compared them with the records of caves and beds of gravel. In this way he has allowed us to peer into the mind of the stone-using savage, who lived at least 240,000 years ago. And the Bible of the Jews, from being a text-book for sermons which bewildered the moral sense even of children, has become, for the study of the great evolution of religion, one of the most valuable books in the world. It bridges the gap between the neolithic or polished-stone-using man and Christ and Mahomet.

Before we go further, let us say a word about the authorship of the Old Testament.

The Books of Moses were compiled by Ezra, at the date of Artaxerxes, the King of the Persians.

It is to be observed that this is not an extravagant guess of German theorists. It is stated authoritatively by Clement of Alexandria. (Strom. 1. 22.) Irenæus, Tertullian, Eusebius, Jerome, and Basil give the same testimony. But a greater authority is behind. It is known that Christ and His disciples, and the early fathers, used the Septuagint or Greek version of the Bible, and Dr. Giles goes so far as to say that there is no hint amongst the latter of the knowledge of even the existence of the Hebrew version. In this Bible (2 Esdras 14.), it is announced distinctly that the “law was burnt;” and that Ezra, aided by the Holy Ghost and “wonderful visions of the night,” wrote down “all that hath been done in the world from the beginning which was written in thy law.”

Let us write down a few dates from the accepted chronology.

| B.C. | |

| Adam | 4004 |

| Abraham | 1996 |

| Moses | 1571 |

| Nebuchadnezzar leads Jews in captivity to Babylon | 587 |

| Jews restored | 517 |

| Ezra | 457 |

Thus the story of Adam in its present form was written down 3547 years after it had occurred. The story of Abraham was written down 1539 years after it occurred. The transactions between Yahve and Moses were written down 1114 years after they occurred.

To gauge the full significance of this, let us call to mind that the poet Tennyson a few years back compiled from old ballads and chronicles the story of Arthur, a king separated from him by about the same gap of time that parted Ezra and Moses. The poet was honest, according to our ideas of honesty, and sought to give a faithful picture of Arthur’s court — with a success that is only moderate. But Ezra was not honest, that is, in our sense of the word. His nation had been a captive of the Babylonians, and had been released from slavery and the lash by Cyrus. In consequence, the molten bulls of the temples of the Jewish taskmasters stank in his nostrils, and led him to advocate the severe nakedness of the Persian fire-altar. And he proposed to do this, not so much by writing new books as by altering the old records and legends, and proclaiming his views through the mouths of the time-honoured patriarchs.

But all this involved a grotesque inference that he seems not to have anticipated. If Abraham, Jacob, Moses, Solomon, knew in their secret hearts that the one fierce hatred of Yahve was the graven image, their assiduous idolatry spread over 1500 years must have been a pure comedy, intended to insult Yahve, not to conciliate him.

What is the object of the religion of the savage? Anthropology has recently answered this question.

The religion of the savage is a slavish reign of terror. His rites and prohibitions are a vast apparatus of magic, to obtain food for the tribe, and safety from the plague and the foeman. In language borrowed from the New Zealander, it is a Great Taboo.

Early man found himself in the presence of the mighty forces of nature. The thunder roared. The lightning struck his rude shelter. A hurricane ruined his crops. The fever or the foeman came upon him. He had to guess the meaning of all this. Some dead chief, much feared in life, is seen in a dream, or his ghost appears. He is silent and looks very sad. What is the cause of his sorrow? Want of food. The early savage knows no other. A storm, a pestilence vexes the clan, and the chief appears again, looking angry. The two facts are connected together. Beasts are slaughtered, and perhaps human victims, and placed near his cairn. The pestilence ceases. In this way the Hottentots have made an ancestor, Tsui Goab, into their god. Indeed, ancestor worship is the basis of all religions. But by and by, to resume our illustration, new calamities vex the tribe. Tsui Goab is angry once more. Fresh efforts are made to soothe him. Soon the Taboo develops into a number of complicated superstitions.

“The savage,” says Sir John Lubbock, “is nowhere free. All over the world his daily life is regulated by a complicated, and often most inconvenient set of customs (as forcible as laws), of quaint prohibitions and privileges…. The Australians are governed by a code of rules and a set of customs which form one of the most cruel tyrannies that has ever, perhaps, existed on the face of the earth.” (“Origin of Civilisation,” p. 304.)

“The lives of savages,” says Mr. Lang, “are bound by the most closely-woven fetters of custom. The simplest acts are ‘tabooed.’ A strict code regulates all intercourse.” (“Custom and Myth.,” p. 72.)

Now, unless this system is clearly understood, Mosaism will remain a riddle. It is to be observed that Ezra, far from having relaxed the reign of terror of the Great Taboo of savage survival, had enlarged the number of petty faults and superstitions; and the Levites and Pharisees at the date of Christ, far from considering all this a comedy, were the most stiff-necked of believers. It results that a new religion that proposed to ignore the chief edicts of the Taboo must have come from some strong outside influence.

The two great foes of the savage, as Mr. Frazer shows in his able work, the “Golden Bough,” were the ghost and the necromancer. The first was deemed all-powerful, and the second sought to use this power to help the tribe and injure its rivals. His art was that of the farmer, the warrior, the doctor—in fact, in his view, pure science. And the laws and ordinances were a Great Taboo, acts forbidden or enjoined to control the ghosts.

Let the Deuteronomist himself tell us what Israel was to expect if she kept these laws and ordinances.

Yahve, it is said, “will love thee, and bless thee, and multiply thee, and he will also bless the fruit of thy womb, and the fruit of thy land, thy corn, and thy wine, and thine oil, the increase of thy kine and the flocks of thy sheep…. The Lord will take away from thee all sickness, and will put none of the evil diseases of Egypt which thou knowest upon thee, but will lay them upon all them that hate thee…. Moreover, the Lord thy God will send the hornet amongst them, until they that are left, and hide themselves from thee, be destroyed.”

This was the religion of Moses. The ghostly head of the clan would give abundant flocks and fertile ground to those who fed him with burnt-offerings, but failing these, would send “the blotch, the itch, the scab” (Deutreonomy. 28. 27), the victorious foeman —and change the fertilising rain to the “powder and dust” of the desert.

“It must be admitted that religion,” says Sir John Lubbock, “as understood by the lower savage races, differs essentially from ours. Thus their deities are evil, not good. They may be forced into compliance with the wishes of man. They require bloody, and rejoice in human sacrifices. They are mortal, not immortal; a part not the author of nature. They are to be approached by dances rather than prayers, and often approve what we call vice rather than what we esteem as virtue.” (“Origin of Civil.,” P133.)

In point of fact, the savage believes that sickness, death, thunder, and other human ills come not from nature, but the active interference of the god. He looks upon every one outside his tribe as an enemy. The west coast negroes represent their deities as “black and mischievous, delighting to torment them in various ways.” The Bechuanas curse their deities when things go wrong. All this throws light on the god of the Hebrews. Professor Robertson Smith, in the new “Encyclopædia Britannica,” describes him as immoral, but perhaps it would be more correct to say that he has the gang morality of a savage chief. He counsels the Jews to borrow the poor silver bangles of the Egyptian women, and then to treacherously carry them off (Exod. 3. 22), because gang morality recognises no rights of property outside the gang. All through the early books, stories of cheating and lying are popular.

Palestine is a narrow strip of land between the Jordan and the Mediterranean, surrounded by deserts. To it, from a city named Ur, in Chaldea, 1996 years B.C., came Abraham and the Hebrews, or “Men from Beyond.” These little Semite clans were like the modern Bedouins. They did not live in towns; they pitched their tents in the country. The soil of Palestine, even in Abraham’s day, was quite unable to support these teeming hordes, for the sons of Abraham went several times to Egypt to escape famine. In similar fashion, ten or twelve thousand Arabs from Tripoli and Bengazi lately left their own country to reach Egypt.

All this must be borne in mind. It has been debated whether the earliest god of Israel was a sun-god or a moon-god, and whether his name was El or Yahve. In point of fact, his name was Starvation, and the Jewish Taboo a great food-making apparatus. This accounts for the extreme ferocity with which the struggle for the land flowing with milk and honey was carried on by the rival tribes.

“When thou comest nigh to a city to fight against it, then proclaim peace to it.

“And it shall be, if it make thee an answer of peace and open unto thee, then it shall be, that all the people that is found therein shall be tributaries unto thee, and they shall serve thee.

“And if it will make no peace with thee, but will make war against thee, then thou shalt besiege it:

“And when the Lord thy God hath delivered it into thy hands, thou shalt smite every male thereof with the edge of the sword;

“But the women, and the little ones, and the cattle, and all that is in the city, even all the spoil thereof, shalt thou take unto thyself: and thou shalt eat the spoil of thine enemies, which the Lord thy God hath given thee.

“Thus shalt thou do unto all the cities which are very far off from thee, which are not of the cities of these nations.”

The “cities that are very far off” mean, in reality, those that are nearer to Moses in the desert than the cities of the promised land, but the writer, composing imaginary laws for Moses in Jerusalem, some hundred years after his death, overlooked this. These are not pretty ones. These cities have to choose at once between slavery or extinction.

“But of the cities of these people, which the Lord thy God doth give thee for an inheritance, thou shalt save alive nothing that breatheth.

“But thou shalt utterly destroy them, namely the Hittites, and the Amorites, the Canaanites and the Perizzites, the Hivites and the Jebusites, as the Lord thy God hath commanded thee.” (Deut. xx. 10-17.)

It accounts, too, for the ferocity of the punishments for the infringement of the Taboo. Death was the penalty. The man who fails to pour dust on the blood of a pigeon that he has knocked down with an arrow, the man who picks up sticks upon the Sabbath, the perfumer who imitates a temple smell, the man who roasts the smallest particle of fat or blood, the labourer who has an abscess and fails to take two turtle doves as a “sin offering” to the priest at “the door of the tabernacle of the congregation” (Levit. xv. 15), may all be cut off. Every one may be stoned for infringing the Taboo.

Sir John Lubbock has pointed out that the god of the savage is of limited power and intelligence, and that the Taboo was designed to control rather than conciliate him. He cites the “Eeweehs” of the Nicobar Islands, who put up scarecrows to frighten their gods, and the inhabitants of Kamtschatka, who insult their deities if their wishes are unfulfilled. He cites also the Rishis and heroes of the Indian epics, who are constantly overcoming the gods of the Indian pantheon. Certainly the early god of the Jew was not deemed all-powerful. When the Jews fought against Askelon it is recorded:—

“The Lord was with Judah, and he drove out the inhabitants of the mountain, but could not drive out the inhabitants of the valley, because they had chariots of iron.” (Judges i. 19.)

He wrestles with Jacob (Gen. xxxii. 29), and the superior wrestling of the man forces the god to give his blessing. He strives to kill Moses, but fails to do it. (Exod. iv. 24.) He is a purely local god, like Kemosh and other Semitic deities.

“Surely Yahve is in this place,” said Jacob in Mesopotamia, “and I knew it not.”

“David himself,” says M. Soury, “who was not and could not have been the monotheistic king of tradition, David, who had teraphim in his house, as had Jacob in his time, does he not seem to restrict the kingdom of Yahve to the land of Israel when he complains that Saul has driven him out from abiding in the inheritance of Yahve, saying, ‘Go, serve other gods’? Finally, many centuries afterwards the contemporaries of Ezekiel still believed that Yahve, having abandoned the country, could no longer see them.” (Ezek. 9. 9.) (Soury, “Religion of Israel,” c.v.)

Anthropology divides the early races who used stone implements into two groups, the palæolithic or rough-stone-using man, and the neolithic man, who polished his implements. The editing of Ezra has burnished up the early Hebrew a little, but it is plain that he had not emerged from the stone age. His god is a stone. Jacob erected a menhir. A menhir is a piece of chipped rock, erect, huge, imposing, the neolithic man’s first rude piece of sculpture, the neolithic man’s god. Moses erected a circle of these stone monoliths. Joshua erected twelve stone gods on the Jordan, and sacrificed to them. (Josh. 4. 9.) Palestine abounds in such circles archæologists tell us. These circles were the “high places” of scripture.

Some hold that the Yahve who travelled with Israel in the Ark was a stone. The mighty God of Jacob is called the “Stone of Israel.” (Gen. xlix. 24.) We read of Eben-ezer, the “Stone of Help,” when the Ark gives the victory to Samuel. (1 Sam. vii. 12.) Daniel’s “stone cut out of the mountain without hands” brake in pieces the kings and the kingdoms. (Dan. ii. 45.) The “Shem Hamphoras,” the stone in the Holy of Holies in Solomon’s temple, was said to be the “Stone of Jacob.”

Circumcision, a savage rite, was performed with “knives of flint.” (Josh. v. 2.) Mr. Tylor (“Early History of Mankind,” p. 216) shows us that even at the date of the Mishna, the beast at the altar was killed with the kelt of the neolithic man. Stones were the official weights in Israel, and also the instruments of execution. David used the sling, and perhaps the chipped stone missiles that we see in museums, and his singing and dancing naked before the fetish, and the very unpleasant scalps that purchased him a wife, savour a little of the latitude of Polynesia. And his hanging up the hands and feet of Rechab and Baanah remind us of the stakes crowned with sculls round the huts of the Dyaks of Borneo.

“At a late date,” says M. Soury, “we perceive in Hebrew legislation the repression of monstrous habits and depraved tastes which are only found amongst the very lowest savages. They are forbidden to tattoo themselves, to eat insects, reptiles,” etc. (Levit. 11. 31; 19. 28.)

I have still to record a quaint use of stones in Israel, another survival from the stone age. In Astley’s “Collection of Voyages” (vol. 2., p. 674,) it is announced that the savages of West Africa consult their god with a sort of “Odd or Even!” with nuts. In Israel, the weightiest questions were settled by the same rude divination. “The pebble is cast into the lap, but the whole disposing thereof is of the Lord.” (Proverbs. 16. 33.) By this odd or even Saul was chosen to be king and Jonah to be thrown overboard. By stones also malefactors were judged in the Holy of Holies, but the exact method of this is a secret that is lost.

In writing thus, of course, I do not believe myself to be dealing with the actual neolithic period. Its survivals are tough. In India before the Mutiny, I was employed with a force sent to put down the rebellion of the Santals. These, a branch of the Kolarias, represent the early races that the Arya displaced. And their institutions were singularly like those of the Jews. They worshipped in “high places” rude circles of upright monoliths. They worshipped in “groves;” and on one occasion we came across a slaughtered kid still warm, that under the holy Sal tree had been sacrificed to obtain the help of Singh Bonga against us. They had, like the Jews, twelve tribes. They believed, like them, that death ended consciousness. They had marriage by capture, softened down into a comedy, like other savage tribes. They believed that all diseases were due to the wrath of evil spirits, or the spell of a sorcerer. All through the night we could hear their war tom-toms sounding, the tuph of the Jews (whence “tympanum,” according to Calmet). They fought with the bows and arrows and axes that are marked “aboriginal weapons” in the South Kensington Museum. When we met them in action a chief came forward like Goliath with gestures and shouts of defiance. Like the Jews they were stiff-necked in their conservatism. Buddhism and Buddha had risen in their very midst. Brahmins, Mussulmans, Christians, had ruled them and plied them with missionaries; but pious Hindoos, instead of converting them, had been persuaded to offer sacrifices to Bagh Bhut, a tiger god, all-powerful in Santal jungles. They recited at night their deeds of theft and pillage and slaughter, like the Sioux Indians or the early Jews.

Circumcision is another savage rite. We find it with the Papuans. We find it in Central America. We find it amongst the Australian aborigines. That it was performed in Israel with knives of flint (Josh. v. 4) argues a survival from the men of stone implements. Sanitary precautions have been suggested as the origin of the rite, but such an idea would be in advance of the filthy savages using it. The “Encyclopædia Britannica” holds that it was a sacrifice to Aschera, the goddess of generation, like a somewhat similar mutilation of females. Professor Sayce (“Ancient Empires,” P199) shows that with young men a complete mutilation in honour of the Phœnician Ashtoreth was common.

Mr. Frazer (“Golden Bough,” i. 169) explains another cruel law of Leviticus. The Maoris believe that if anyone touches a dead body, and then accidentally touches food, any one partaking of that food will join the dead man in the shades. This superstition about the power of the dead is the root idea of other practices, covering pictures and looking-glasses whilst the corpse is still in the house, shunning the graveyard at night when it is buried. It is treated as an enemy who might pass his soul into the picture and do mischief. The death penalty for touching Yahve’s food (Levit. vii. 21) is probably the same superstition. When God is supposed to be walking about on earth in human form, as in the instance of a semi-divine savage chief, the danger of touching his food increases enormously. Mr. Frazer shows that the Mikado used to eat every day off new rude earthenware platters, which were at once broken and buried, that no one might lose his life by accidentally touching a particle of his food. (“Golden Bough,” 1. 166.) Mr. Frazer gives numerous instances, where the same fatality is believed to result from food contaminated by a menstruous woman.

In the view of M. Soury, the early Jew was a tattooed savage, who ate insects; but anthropology has shed an unexpected light on this. The families, and small clans of early savages, had each some animal as a Totem. They were tattooed with this for distinction, and it was everywhere ruled that cat could not marry cat, or fox fox. A young man tattooed as a fox would have to capture a lady with another crest, “stunning her first with a blow from his dowak” perchance, like the Australian savage described by Sir John Lubbock.

It has been shown by Professor Robertson Smith that the “unclean” animals of the Old Testament are these totems. “So I went in and saw, and behold every form of creeping things and abominable beasts and all the idols of the house of Israel pourtrayed upon the wall round about.” (Ezek. 8. 10.) This accounts for the hare being “abominable” in Israel, and the beetle edible. It was meritorious to eat the totems of one’s foes, but the totems of friendly tribes, and one’s own totems, were tabooed. The origin of these ideas is much debated. The custom is believed to be closely connected with marriage by capture. Female infanticide was prevalent, as women only attracted ravishers. The story of the sons of Benjamin capturing the daughters of Shiloh is a frequent sort of story in savage annals. (Judges xxi.)

The sacrifice has puzzled the modern divine.

It is urged that rites are necessary to religion, and that the sacrifice was an apparatus to train Israel to a deep sense of sin, and a necessity for a blood atonement. It is contended that it was merely a form, as only the useless portions of the carcase were given to Yahve. Those who talk like this libel the Jewish patriarchs. With savages the blood and the fat are considered the choicest morsels. To stone a poor Jew because he ate a little fat with his supper would have been infamous, if the whole affair was a harmless comedy. We have shown that the one thought of the Jew was a mighty terror, a Great Taboo. Starvation or rich harvests, victory or slavery, were due direct to Yahve; and the bloody sacrifice was the one and sole instrument by which he might be controlled.

As late as Leviticus it was believed that the burnt-offering actually provided food and drink to the Maker of the universe. It is called the “food of God” (Levit. 21. 8), a phrase softened into “bread of God” in our version, as the “Encyclopædia Britannica” (article “Bible”) has shown. It was believed also that God specially loved the smell. (Leviticus. 8. 21.) More important still, as pointed out by Sir John Lubbock in his “Origin of Civilisation,” p. 272, human sacrifices are expressly ordered in Leviticus (27. 28, 29):—

“Notwithstanding, no devoted thing that a man shall devote unto the Lord, of all that he hath, both of man and beast, and of the field of his possession, shall be sold or redeemed: every devoted thing is most holy unto the Lord.

“None devoted, which shall be devoted of men, shall be redeemed, but shall surely be put to death.”

“There is indeed no doubt that human victims were offered to Yahve,” says M. Soury. “The young of man belonged to Yahve, just as did the young of the animal and the fruit of the tree. All the gods of the Semites, —El, Schaddai, Adon, Baal, Moloch, Yahve, Kemosh, — were conceived in the likeness of Eastern monarchs. They had right absolute over all that was born and all that died in their realms. Man admits his vassalage. He adores the ‘master,’ and brings to his lord the first-fruits of his flock, his field, and his family.” (“Religion of Israel,” c. vi.)

The French author goes on to say that during their sojourn in Egypt the Jews sacrificed human victims. (Ezek. 20. 26.) “In all the history of religions there is no human sacrifice better established than that of the daughter of Jephthah to Yahve. In the time of the Judges, who does not know the story of Samuel and Agag? It is ‘before Yahve,’ at Gilgal, that Samuel kills his victim. David appeased the wrath of Yahve, who had afflicted the land with famine during three years, by delivering up to the Gibeonites seven men of Saul’s blood. The seven victims being hanged ‘on the hill before Yahve,’ the deity was satisfied.” (2 Sam. xxi. 1-14.)

This human sacrifice is, of course, a survival of cannibalism. The Australians, as Lumholtz (“Among Cannibals,” P70) shows, consider “talgoro” (human flesh) the daintiest of food. At their watchfires they discourse upon the delicate fat round the kidneys as an alderman might talk of calipash.

What is all this leading up to? Simply to this, that we must put far away from us the theory of modern pulpits that the bloody sacrifice was a comedy of the priest, a comedy of the Almighty. The sacrifice was not a comedy at all. To the mind of the savage it was at once business and science. It was the bank, the war office, the bureau of agriculture, the college of physicians of the nation. By it alone could the blood-loving Semite gods be influenced to give harvests, shekels, victory; and the ferocious Taboo was pure science likewise. The archer, for instance, who killed a partridge without covering the blood with earth was killed in turn, because the Taboo was a mechanism that could only be kept in working order by a remorseless attention to its most minute rules. Writers like Kuenen and Lightfoot assure us that it is quite impossible that Christianity can be due to any influence outside Judaism, because it is such a very obvious development of Jewish thought. This is a startling statement. Christianity pronounced the slaughter of animals at the altar a piece of useless folly, and tore up the great ordinances of Taboo, the Covenant between Israel and the Maker of the Heavens. It proclaimed three Gods instead of one. It pronounced that the Jewish holy books were parables rather than a statement of actual facts. Such ideas were at this epoch current in the West, owing to the activity of the missionaries of an Eastern creed.

To them we will now turn.

Chapter 2.

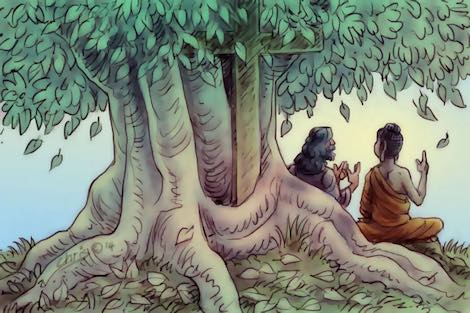

Buddha.

I propose now to give a short life of Buddha, noting its points of contact with that of Jesus.

PRE-EXISTENCE IN HEAVEN.

The early Buddhists, following the example of the Vedic Brahmins, divided space into Nirvritti, the dark portion of the heavens, and Pravritti, the starry systems. Over this last, the luminous portion, Buddha figures as ruler when the legendary life opens. The Christian Gnostics took over this idea and gave to Christ a similar function. Buthos was Nirvritti ruled by “The Father” (in Buddhism by Swayambhu, the self-existent), Pravritti was the Pleroma. “It was the Father’s good pleasure that in him the whole Pleroma should have its home.” (Col. 1. 19.)

“BEHOLD A VIRGIN SHALL CONCEIVE.”

Exactly 550 years before Christ there dwelt in North Oude, at a city called Kapilavastu, the modern Nagar Khas, a king called Suddhodana. This monarch was informed by angels that a mighty teacher of men would be born miraculously in the womb of his wife. “By the consent of the king,” says the “Lalita Vistara,” “the queen was permitted to lead the life of a virgin for thirty-two months.” Joseph is made, a little awkwardly, to give a similar privilege to his wife. (Matt. i. 25.)

Some writers have called in question the statement that Buddha was born of a virgin, but in the southern scriptures, as given by Mr. Turnour, it is announced that a womb in which a Buddha elect has reposed, is like the sanctuary of a temple. On that account, that her womb may be sacred, the mother of a Buddha always dies in seven days. The name of the queen was borrowed from Brahminism. She was Mâyâ Devî, the Queen of Heaven. And one of the titles of this lady is Kanyâ, the Virgin of the Zodiac.

Queen Mâyâ was chosen for her mighty privilege because the Buddhist scriptures announce that the mother of a Buddha must be of royal line.

Long genealogies, very like those of the New Testament, are given also to prove the blue blood of King Suddhodana, who, like Joseph, had nothing to do with the paternity of the child. “King Mahasammata had a son named Roja, whose son was Vararoja, whose son was Kalyâna, whose son was Varakalyâna,” and so on, and so on. (Dîpawanso, see “Journ. As. Soc.,” Bengal, vol. vii., P925.)

How does a Buddha come down to earth? This question is debated in Heaven, and the Vedas were searched because, as Seydel shows, although Buddhism seemed a root and branch change, it was attempted to show that it was really the lofty side of the old Brahminism, a lesson not lost by and by in Palestine. The sign of Capricorn in the old Indian Zodiac is an elephant issuing from a Makara (leviathan), and it symbolises the active god issuing from the quiescent god in his home on the face of the waters. In consequence, Buddha comes down as a white elephant, and enters the right side of the queen without piercing it or in any way injuring it. Childers sees a great analogy in all this to the Catholic theory of the perpetual virginity of Mary. Catholic doctors quote this passage from Ezekiel (xliv. 2):—

“Then said the Lord unto me, This gate shall be shut, it shall not be opened, and no man shall enter in by it; because the Lord, the God of Israel, hath entered in by it, therefore shall it be shut.”

A DOUBLE ANNUNCIATION.

It is recorded that when Queen Mâyâ received the supernal Buddha in her womb, in the form of a beautiful white elephant, she said to her husband: “Like snow and silver, outshining the sun and the moon, a white elephant of six defences, with unrivalled trunk and feet, has entered my womb. Listen, I saw the three regions (earth, heaven, hell,) with a great light shining in the darkness, and myriads of spirits sang my praises in the sky.”

A similar miraculous communication was made to King Suddhodana:—

“The spirits of the Pure Abode flying in the air, showed half of their forms, and hymned King Suddhodana thus:

“Guerdoned with righteousness and gentle pity,

Adored on earth and in the shining sky,

The coming Buddha quits the glorious spheres

And hies to earth to gentle Mâyâ’s womb.”

In the Christian scriptures there is also a double annunciation. In Luke (i. 28) the angel Gabriel is said to have appeared to the Virgin Mary before her conception, and to have foretold to her the miraculous birth of Christ. But in spite of this astounding miracle, Joseph seems to have required a second personal one before he ceased to question the chastity of his wife. (Matt. i. 19.) Plainly, two evangelists have been working the same mine independently, and a want of consistency is the result.

When Buddha was in his mother’s womb that womb was transparent. The Virgin Mary was thus represented in mediæval frescoes. (See illustration, P39, in my “Buddhism in Christendom.”)

“WE HAVE SEEN HIS STAR IN THE EAST.”

In the Buddhist legend the devas in heaven announce that Buddha will be born when the Flower-star is seen in the East. (Lefman, xxi. 124; Wassiljew, P95.)

Amongst the thirty-two signs that indicate the mother of a Buddha, the fifth is that, like Mary the mother of Jesus, she should be “on a journey” (Beal, “Rom. History,” P32) at the moment of parturition. This happened. A tree (palâsa, the scarlet butea) bent down its branches and overshadowed her, and Buddha came forth. Voltaire says that in the library of Berne there is a copy of the First Gospel of the Infancy, which records that a palm tree bent down in a similar manner to Mary. (“Œuvres,” vol. xl.) The Koran calls it a “withered date tree.”

In the First Gospel of the Infancy, it is stated that, when Christ was in His cradle, He said to His mother: “I am Jesus, the Son of God, the Word whom thou didst bring forth according to the declaration of the angel Gabriel to thee, and my Father hath sent Me for the salvation of the world.”

In the Buddhist scriptures it is announced that Buddha, on seeing the light, said:—

“I am in my last birth. None is my equal. I have come to conquer death, sickness, old age. I have come to subdue the spirit of evil, and give peace and joy to the souls tormented in hell.”

In the same scriptures (see Beal, “Rom. History,” P46) it is announced that at the birth of the Divine child, the devas (angels) in the sky sang “their hymns and praises.”

CHILD-NAMING.

“Five days after the birth of Buddha,” says Bishop Bigandet, in the “Burmese Life,” “was performed the ceremony of head ablution and naming the child.” (P49.)

We see from this where the ceremony of head ablution and naming the child comes from. In the “Lalita Vistara” Buddha is carried to the temple. Plainly we have the same ceremony. There the idols bow down to him as in the First Gospel of the Infancy the idol in Egypt bows down to Jesus. In Luke the infant Jesus is also taken to the temple by his parents to “do for him after the custom of the law.” (Luke ii. 27.) What law? Certainly not the Jewish.

HEROD AND THE WISE MEN.

It is recorded in the Chinese life (Beal, “Rom. History,” P103) that King Bimbisâra, the monarch of Râjagriha, was told by his ministers that a boy was alive for whom the stars predicted a mighty destiny. They advised him to raise an army and go and destroy this child, lest he should one day subvert the king’s throne. Bimbisâra refused.

At the birth of Buddha the four Mahârâjas, the great kings, who in Hindoo astronomy guard each a cardinal point, received him. These may throw light on the traditional Persian kings that greeted Christ.

In some quarters these analogies are admitted, but it is said that the Buddhists copied from the Christian scriptures. But this question is a little complicated by the fact that many of the most noticeable similarities are in apocryphal gospels, those that were abandoned by the Church at an early date. In the Protevangelion, at Christ’s birth, certain marvels are visible. The clouds are “astonished,” and the birds of the air stop in their flight. The dispersed sheep of some shepherds near cease to gambol, and the shepherds to beat them. The kids near a river are arrested with their mouths close to the water. All nature seems to pause for a mighty effort. In the “Lalita Vistara” the birds also pause in their flight when Buddha comes to the womb of Queen Mâyâ. Fires go out, and rivers are suddenly arrested in their flow.

More noticeable is the story of Asita, the Indian Simeon.

Asita dwells on Himavat, the holy mount of the Hindoos, as Simeon dwells on Mount Zion. The “Holy Ghost is upon” Simeon. That means that he has obtained the faculties of the prophet by mystical training. He “comes by the Spirit” into the temple. Asita is an ascetic, who has acquired the eight magical faculties, one of which is the faculty of visiting the Tawatinsa heavens. Happening to soar up into those pure regions one day, he is told by a host of devatas, or heavenly spirits, that a mighty Buddha is born in the world, “who will establish the supremacy of the Buddhist Dharma.” The “Lalita Vistara” announces that, “looking abroad with his divine eye, and considering the kingdoms of India, he saw in the great city of Kapilavastu, in the palace of King Suddhodana, the child shining with the glitter of pure deeds, and adored by all the worlds.” Afar through the skies the spirits of heaven in crowds recited the “hymn of Buddha.”

This is the description of Simeon in the First Gospel of the Infancy, ii. 6—”At that time old Simeon saw Him (Christ) shining as a pillar of light when St. Mary the Virgin, His mother, carried Him in her arms, and was filled with the greatest pleasure at the sight. And the angels stood around Him, adoring Him as a King; guards stood around Him.”

Asita pays a visit to the king. Asita takes the little child in his arms. Asita weeps.

“Wherefore these tears, O holy man?”

“I weep because this child will be the great Buddha, and I shall not be alive to witness the fact.”

The points of contact between Simeon and Asita are very close. Both are men of God, “full of the Holy Ghost.” Both are brought “by the Spirit” into the presence of the Holy Child, for the express purpose of foretelling His destiny as the Anointed One.

More remarkable still is the incident of the disputation with the doctors.

A little Brahmin was “initiated,” girt with the holy thread, etc., at eight, and put under the tuition of a holy man. When Vis’vâmitra, Buddha’s teacher, proposed to teach him the alphabet, the young prince went off:—

“In sounding ‘A,’ pronounce it as in the sound of the word ‘anitya.’

“In sounding ‘I,’ pronounce it as in the word ‘indriya.’

“In sounding ‘U,’ pronounce it as in the word ‘upagupta.'”

And so on through the whole Sanscrit alphabet.

In the First Gospel of the Infancy, chapter 20., it is recorded that when taken to the schoolmaster Zaccheus, “The Lord Jesus explained to him the meaning of the letters Aleph and Beth.

“8. Also, which were the straight figures of the letters, which were the oblique, and what letters had double figures; which had points and which had none; why one letter went before another; and many other things He began to tell him and explain, of which the master himself had never heard, nor read in any book.

“9. The Lord Jesus further said to the master, Take notice how I say to thee. Then He began clearly and distinctly to say Aleph, Beth, Gimel, Daleth, and so on to the end of the alphabet.

“10. At this, the master was so surprised, that he said, I believe this boy was born before Noah.”

In the “Lalita Vistara” there are two separate accounts of Buddha showing his marvellous knowledge. His great display is when he competes for his wife. He then exhibits his familiarity with all lore, sacred and profane, “astronomy,” the “syllogism,” medicine, mystic rites.

The disputation with the doctors is considerably amplified in the twenty-first chapter of the First Gospel of the Infancy:—

“5. Then a certain principal rabbi asked Him, Hast Thou read books?

“6. Jesus answered that He had read both books and the things which were contained in books.

“7. And he explained to them the books of the law and precepts and statutes, and the mysteries which are contained in the books of the prophets—things which the mind of no creature could reach.

“8. Then said that rabbi, I never yet have seen or heard of such knowledge! What do you think that boy will be?

“9. Then a certain astronomer who was present asked the Lord Jesus whether He had studied astronomy.

“10. The Lord Jesus replied, and told him the number of the spheres and heavenly bodies, as also their triangular, square, and sextile aspects, their progressive and retrograde motions, their size and several prognostications, and other things which the reason of man had never discovered.

“11. There was also among them a philosopher, well skilled in physic and natural philosophy, who asked the Lord Jesus whether He had studied physic.

“12. He replied, and explained to him physics and metaphysics.

“13. Also those things which were above and below the power of nature.

“14. The powers also of the body, its humours and their effects.

“15. Also the number of its bones, veins, arteries, and nerves.

“16. The several constitutions of body, hot and dry, cold and moist, and the tendencies of them.

“17. How the soul operated on the body.

“18. What its various sensations and faculties were.

“19. The faculty of speaking, anger, desire.

“20. And, lastly, the manner of its composition and dissolution, and other things which the understanding of no creature had ever reached.

“21. Then that philosopher worshipped the Lord Jesus, and said, O Lord Jesus, from henceforth I will be Thy disciple and servant.”

Vis´vâmitra in like manner worshipped Buddha by falling at his feet.

THE MYSTERIES OF THE KINGDOM OF HEAVEN.

I have now come to a stage in this narrative when a few remarks are necessary. The “Lalita Vistara” professes to reveal the secrets of the Buddhas, the secrets of “magic,” the secrets of Yoga, or union with Brahma. And whether it be fiction or history, it does so more roundly than any other work. The Christian gospels profess also to teach a similar secret. Read by the light of the Buddhist book, I think they do teach it. But read alone, eighteen centuries come forward to show that they do not.

The highest spiritual philosophers in Buddhism, in Brahminism, in Christendom, in Islam, announce two kingdoms distinct from one another. They are called in India the Domain of Appetite (Kâmaloca), and the Domain of Spirit (Brahmaloca). The “Lalita Vistara” throughout describes a conflict between these two great camps. Buddha is offered a crown by his father. He has wives, palaces, jewels, but he leaves all for the thorny jungle where the Brahmacharin dreamt his dreams of God. This is called pessimism by some writers, who urge that we should enjoy life as we find it, but modern Europe having tried, denies that life is so enjoyable. Its motto is Tout lasse, tout casse, tout passe. Yes, say the optimists, but we needn’t all live a life like Jay Gould. A good son, a good father, a good husband, a good citizen, is happy enough. True, reply the pessimists, in so far as a mortal enters the domain of spirit he may be happy, for that is not a region but a state of the mind. But mundane accidents seem, almost by rule, to mar even that happiness. The husband loses his loved one, the artist his eyesight. Philosophers and statesmen find their great dreams and schemes baffled by the infirmities of age.

Age, disease, death! These are the evils for which the great Indian allegory proposes to find a remedy. Let us see what that remedy is.

Chapter 3.

The Four Presaging Tokens.

Soothsayers were consulted by King Suddhodana. They pronounced the following:—

“The young boy will, without doubt, be either a king of kings, or a great Buddha. If he is destined to be a great Buddha, four presaging tokens will make his mission plain. He will see—

“1. An old man.

“2. A sick man.

“3. A corpse.

“4. A holy recluse.

“If he fails to see these four presaging tokens of an avatâra, he will be simply a Chakravartin” (king of earthly kings).

King Suddhodana, who was a trifle worldly, was very much comforted by the last prediction of the soothsayers. He thought in his heart, It will be an easy thing to keep these four presaging tokens from the young prince. So he gave orders that three magnificent palaces should at once be built—the Palace of Spring, the Palace of Summer, the Palace of Winter. These palaces, as we learn from the “Lalita Vistara,” were the most beautiful palaces ever conceived on earth. Indeed, they were quite able to cope in splendour with Vaijayanta, the immortal palace of Indra himself. Costly pavilions were built out in all directions, with ornamented porticoes and burnished doors. Turrets and pinnacles soared into the sky. Dainty little windows gave light to the rich apartments. Galleries, balustrades, and delicate trellis-work were abundant everywhere. A thousand bells tinkled on each roof. We seem to have the lacquered Chinese edifices of the pattern which architects believe to have flourished in early India. The gardens of these fine palaces rivalled the chess-board in the rectangular exactitude of their parterres and trellis-work bowers. Cool lakes nursed on their calm bosoms storks and cranes, wild geese and tame swans; ducks, also, as parti-coloured as the white, red, and blue lotuses amongst which they swam. Bending to these lakes were bowery trees—the champak, the acacia serisha, and the beautiful asoka tree with its orange-scarlet flowers. Above rustled the mimosa, the fan-palm, and the feathery pippala, Buddha’s tree. The air was heavy with the strong scent of the tuberose and the Arabian jasmine.

It must be mentioned that strong ramparts were prepared round the palaces of Kapilavastu, to keep out all old men, sick men, and recluses, and, I must add, to keep in the prince.

And a more potent safeguard still was designed. When the prince was old enough to marry, his palace was deluged with beautiful women. He revelled in the “five dusts,” as the Chinese version puts it. But a shock was preparing for King Suddhodana.

This is how the matter came about. The king had prepared a garden even more beautiful than the garden of the Palace of Summer. A soothsayer had told him that if he could succeed in showing the prince this garden, the prince would be content to remain in it with his wives for ever. No task seemed easier than this, so it was arranged that on a certain day the prince should be driven thither in his chariot. But, of course, immense precautions had to be taken to keep all old men and sick men and corpses from his sight. Quite an army of soldiers were told off for this duty, and the city was decked with flags. The path of the prince was strewn with flowers and scents, and adorned with vases of the rich kadali plant. Above were costly hangings and garlands, and pagodas of bells.

But, lo and behold! as the prince was driving along, plump under the wheels of his chariot, and before the very noses of the silken nobles and the warriors with javelins and shields, he saw an unusual sight. This was an old man, very decrepit and very broken. The veins and nerves of his body were swollen and prominent; his teeth chattered; he was wrinkled, bald, and his few remaining hairs were of dazzling whiteness; he was bent very nearly double, and tottered feebly along, supported by a stick.

“What is this, O coachman?” said the prince. “A man with his blood all dried up, and his muscles glued to his body! His head is white; his teeth knock together; he is scarcely able to move along, even with the aid of that stick!”

“Prince,” said the coachman, “this is Old Age. This man’s senses are dulled; suffering has destroyed his spirit; he is contemned by his neighbours. Unable to help himself, he has been abandoned in this forest.”

“Is this a peculiarity of his family?” demanded the prince, “or is it the law of the world? Tell me quickly.”

“Prince,” said the coachman, “it is neither a law of his family, nor a law of the kingdom. In every being youth is conquered by age. Your own father and mother and all your relations will end in old age. There is no other issue to humanity.”

“Then youth is blind and ignorant,” said the prince, “and sees not the future. If this body is to be the abode of old age, what have I to do with pleasure and its intoxications? Turn round the chariot, and drive me back to the palace!”

Consternation was in the minds of all the courtiers at this untoward occurrence; but the odd circumstance of all was that no one was ever able to bring to condign punishment the miserable author of the mischief. The old man could never be found.

King Suddhodana was at first quite beside himself with tribulation. Soldiers were summoned from the distant provinces, and a cordon of detachments thrown out to a distance of four miles in each direction, to keep the other presaging tokens from the prince. By and by the king became a little more quieted. A ridiculous accident had interfered with his plans: “If my son could see the Garden of Happiness he never would become a hermit.” The king determined that another attempt should be made. But this time the precautions were doubled.

On the first occasion the prince left the Palace of Summer by the eastern gate. The second expedition was through the southern gate.

But another untoward event occurred. As the prince was driving along in his chariot, suddenly he saw close to him a man emaciated, ill, loathsome, burning with fever. Companionless, uncared for, he tottered along, breathing with extreme difficulty.

“Coachman,” said the prince, “what is this man, livid and loathsome in body, whose senses are dulled, and whose limbs are withered? His stomach is oppressing him; he is covered with filth. Scarcely can he draw the breath of life!”

“Prince,” said the coachman, “this is Sickness. This poor man is attacked with a grievous malady. Strength and comfort have shunned him. He is friendless, hopeless, without a country, without an asylum. The fear of death is before his eyes.”

“If the health of man,” said Buddha, “is but the sport of a dream, and the fear of coming evils can put on so loathsome a shape, how can the wise man, who has seen what life really means, indulge in its vain delights? Turn back, coachman, and drive me to the palace!”

The angry king, when he heard what had occurred, gave orders that the sick man should be seized and punished, but although a price was placed on his head, and he was searched for far and wide, he could never be caught. A clue to this is furnished by a passage in the “Lalita Vistara.” The sick man was in reality one of the Spirits of the Pure Abode, masquerading in sores and spasms. These Spirits of the Pure Abode are also called the Buddhas of the Past, in many passages. The answers of the coachman were due to their inspiration.

It would almost seem as if some influence, malefic or otherwise, was stirring the good King Suddhodana. Unmoved by failure, he urged the prince to a third effort. The chariot this time was to set out by the western gate. Greater precautions than ever were adopted. The chain of guards was posted at least twelve miles off from the Palace of Summer. But the Buddhas of the Past again arrested the prince. His chariot was suddenly crossed by a phantom funeral procession. A phantom corpse, smeared with the orthodox mud, and spread with a sheet, was carried on a bier. Phantom women wailed, and phantom musicians played on the drum and the Indian flute. No doubt also, phantom Brahmins chanted hymns to Jatavedas, to bear away the immortal part of the dead man to the home of the Pitris.

“What is this?” said the prince. “Why do these women beat their breast and tear their hair? Why do these good folks cover their heads with the dust of the ground? And that strange form upon its litter, wherefore is it so rigid?”

“Prince,” said the charioteer, “this is Death! Yon form, pale and stiffened, can never again walk and move. Its owner has gone to the unknown caverns of Yama. His father, his mother, his child, his wife cry out to him, but he cannot hear.”

Buddha was sad.

“Woe be to youth, which is the sport of age! Woe be to health, which is the sport of many maladies! Woe be to life, which is as a breath! Woe be to the idle pleasures which debauch humanity! But for the ‘five aggregations’ there would be no age, sickness, nor death. Go back to the city. I must compass the deliverance.”

A fourth time the prince was urged by his father to visit the Garden of Happiness. The chain of guards this time was sixteen miles away. The exit was by the northern gate. But suddenly a calm man of gentle mien, wearing an ochre-red cowl, was seen in the roadway.

“Who is this,” said the prince, “rapt, gentle, peaceful in mien? He looks as if his mind were far away elsewhere. He carries a bowl in his hand.”

“Prince, this is the New Life,” said the charioteer. “That man is of those whose thoughts are fixed on the eternal Brahma [Brahmacharin]. He seeks the divine voice. He seeks the divine vision. He carries the alms-bowl of the holy beggar [bhikshu]. His mind is calm, because the gross lures of the lower life can vex it no more.”

“Such a life I covet,” said the prince. “The lusts of man are like the sea-water—they mock man’s thirst instead of quenching it. I will seek the divine vision, and give immortality to man!”

King Suddhodana was beside himself. He placed five hundred corseleted Sakyas at every gate of the Palace of Summer. Chains of sentries were round the walls, which were raised and strengthened. A phalanx of loving wives, armed with javelins, was posted round the prince’s bed to “narrowly watch” him. The king ordered also all the allurements of sense to be constantly presented to the prince.

“Let the women of the zenana cease not for an instant their concerts and mirth and sports. Let them shine in silks and sparkle in diamonds and emeralds.”

The allegory is in reality a great battle between two camps—the denizens of the Kâmaloca, or the Domains of Appetite, and the denizens of the Brahmaloca, the Domains of Pure Spirit. The latter are unseen, but not unfelt.

For one day, when the prince reclined on a silken couch listening to the sweet crooning of four or five brown-skinned, large-eyed Indian girls, his eyes suddenly assumed a dazed and absorbed look, and the rich hangings and garlands and intricate trellis-work of the golden apartment were still present, but dim to his mind. And music and voices, more sweet than he had ever listened to, seemed faintly to reach him. I will write down some of the verses.

“Mighty prop of humanity

March in the pathway of the Rishis of old,

Go forth from this city!

Upon this desolate earth,

When thou hast acquired the priceless knowledge of the Jinas,

When thou hast become a perfect Buddha,

Give to all flesh the baptism (river) of the kingdom of Righteousness,

Thou who once didst sacrifice thy feet, thy hands, thy precious body, and all thy riches for the world,

Thou whose life is pure, save flesh from its miseries!

In the presence of reviling be patient, O conqueror of self!

Lord of those who possess two feet, go forth on thy mission!

Conquer the evil one and his army.”

In the end the Buddhas of the Past triumph. They persuade Buddha to flee away from his cloying pleasures and become a Yogi.

“THEN WAS JESUS LED UP BY THE SPIRIT INTO THE WILDERNESS, TO BE TEMPTED OF THE DEVIL.”

Comfortable dowagers driving to church three times on Sunday would be astonished to learn that the essence of Christianity is in this passage. Its meaning has quite passed away from Protestantism, almost from Christendom. The “Lalita Vistara” fully shows what that meaning is. Without Buddhism it would be lost. Jesus was an Essene, and the Essene, like the Indian Yogi, sought to obtain divine union and the “gifts of the Spirit” by solitary reverie in retired spots. In what is called the “Monastery of our Lord” on the Quarantania, a cell is shown with rude frescoes of Jesus and Satan. There, according to tradition, the demoniac hauntings that all mystics speak of occurred.

“I HAVE NEED TO BE BAPTISED OF THEE.”

A novice in Yoga has a guru, or teacher. Buddha, in riding away from the palace by and by reached a jungle near Vaisalî. He at once put himself under a Brahmin Yogi named Arâta Kâlâma, but his spiritual insight developed so rapidly that in a short time the Yogi offered to Buddha, the arghya, the offering of rice, flowers, sesamun, etc., that the humble novice usually presents to his instructor, and asked him to teach instead of learning. (Foucaux, “Lalita Vistara,” P228.)

THIRTY YEARS OF AGE.

M. Ernest de Bunsen, in his work, “The Angel Messiah,” says that Buddha, like Christ, commenced preaching at thirty years of age. He certainly must have preached at Vaisalî, for five young men became his disciples there, and exhorted him to go on with his teaching. (“Lalita Vistara,” P236.) He was twenty-nine when he left the palace, therefore he might well have preached at thirty. He did not turn the wheel of the law until after a six years’ meditation under the Tree of Knowledge.

BAPTISM.

The Buddhist rite of baptism finds its sanction in two incidents in the Buddhist scriptures. In the first, Buddha bathes in the holy river, and Mâra, the evil spirit, tries to prevent him from emerging. In the second, angels administer the holy rite (Abhisheka).

“AND WHEN HE HAD FASTED FORTY DAYS AND FORTY NIGHTS.”

Buddha, immediately previous to his great encounter with Mâra, the tempter, fasted forty-nine days and nights. (“Chinese Life,” by Wung Puh.)

“COMMAND THAT THESE STONES BE MADE BREAD.”

The first temptation of Buddha, when Mâra assailed him under the bo tree, is precisely similar to that of Jesus. His long fast had very nearly killed him. “Sweet creature, you are at the point of death. Sacrifice food.” This meant, eat a portion to save your life.

“AGAIN THE DEVIL TAKETH HIM UP INTO AN EXCEEDING HIGH MOUNTAIN,” ETC.

The second temptation of Mâra is also like one of Satan’s. The tempter, by a miracle, shows Buddha the glorious city of Kapilavastu, twisting the earth round like the “wheel of a potter” to do this. He offers to make him a mighty king of kings (Chakravartin) in seven days. (Bigandet, P65.)

THE THIRD TEMPTATION.

Jewish prudery has quite marred the third temptation. From the days of Krishna and the phantom naked woman, Kotavî, to the days of St. Anthony and St. Jerome, or even to the days of mediæval monasteries with their incubi and succubi, sex temptations have been a prominent feature of the fasting ascetic’s visions. The daughters of Mâra, the tempter, in exquisite forms, now come round Buddha. In the end he converts these pretty ladies, and converts and baptises Mâra himself.

“AND ANGELS CAME AND MINISTERED UNTO HIM.”

After his conflict with Mâra, angels come to greet him.

“GLAD TIDINGS OF GREAT JOY.”

Buddha, on vanquishing Mâra, left Buddha Gaya for the deer forest of Benares. There he began to preach. His doctrine is called Subha Shita (glad tidings). (See Rajendra L. Mitra “N. Buddhist Lit.,” P29.)

“BEHOLD A GLUTTONOUS PERSON!”

Five disciples who left him when he gave over the rigid fasts of the Brahmins, called out on seeing him in the deer forest, “Behold a gluttonous person!” (relaché et gourmand).

“FOLLOW ME.”

Almost his first converts were thirty profligate young men, whom he met sporting with lemans in the Kappasya jungle. “He received them,” says Professor Rhys Davids, “into the order, with the formula, ‘Follow Me.'” (“Birth Stories,” P114.)

THE TWELVE GREAT DISCIPLES.

“Except in my religion, the twelve great disciples are not to be found.” (Bigandet, P301.)

“THE DISCIPLE WHOM JESUS LOVED.”

One disciple was called Upatishya (the beloved disciple). In a former existence, he and Maudgalyâyana had prayed that they might sit, the one on the right hand and the other on the left. Buddha granted this prayer. The other disciples murmured much. (Bigandet, P153.)

“GO YE INTO ALL THE WORLD.”

From Benares Buddha sent forth the sixty-one disciples. “Go ye forth,” he said, “and preach Dharma, no two disciples going the same way.” (Bigandet, P126.)

“THE SAME CAME TO JESUS BY NIGHT.”

Professor Rhys Davids points out that Yâsas, a young rich man, came to Buddha by night for fear of his rich relations.

PAX VOBISCUM.

On one point I have been a little puzzled. The password of the Buddhist Wanderers was Sadhu! which does not seem to correspond with the “Pax Vobiscum!” (Matt. x. 13) of Christ’s disciples. But I have just come across a passage in Renan (“Les Apôtres,” P22) which shows that the Hebrew word was Schalom! (bonheur!) This is almost a literal translation of Sadhu!

Burnouf says that by preaching and miracle Buddha’s religion was established. In point of fact it was the first universal religion. He invented the preacher and the missionary.

“A NEW COMMANDMENT GIVE I YOU, THAT YE LOVE ONE ANOTHER.”

“By love alone can we conquer wrath. By good alone can we conquer evil. The whole world dreads violence. All men tremble in the presence of death. Do to others that which ye would have them do to you. Kill not. Cause no death.” (“Sûtra of Forty-two Sections,” v. 129.)

“Say no harsh words to thy neighbour. He will reply to thee in the same tone.” (Ibid. v. 133.)

“‘I am injured and provoked, I have been beaten and plundered!’ They who speak thus will never cease to hate.” (Ibid. v. 4, 5.)

“That which can cause hate to cease in the world is not hate, but the absence of hate.”

“If, like a trumpet trodden on in battle, thou complainest not, thou has attained Nirvâna.”

“Silently shall I endure abuse, as the war-elephant receives the shaft of the bowman.”

“The awakened man goes not on revenge, but rewards with kindness the very being who has injured him, as the sandal tree scents the axe of the woodman who fells it.”

THE BEATITUDES.

The Buddhists, like the Christians, have got their Beatitudes. They are plainly arranged for chant and response in the temples. It is to be noted that the Christian Beatitudes were a portion of the early Christian ritual.

“An Angel.

“1 Many angels and men

Have held various things blessings.

When they were yearning for the inner wisdom

Do thou declare to us the chief good.

“Buddha.

“2 Not to serve the foolish,

But to serve the spiritual;

To honour those worthy of honour,—

This is the greatest blessing.

“3 To dwell in a spot that befits one’s condition,

To think of the effect of one’s deeds,

To guide the behaviour aright,—

This is the greatest blessing.

“4 Much insight and education,

Self-control and pleasant speech,

And whatever word be well spoken,—

This is the greatest blessing.

“5 To support father and mother,

To cherish wife and child,

To follow a peaceful calling,—

This is the greatest blessing.

“6 To bestow alms and live righteously

To give help to kindred,

Deeds which cannot be blamed,—

These are the greatest blessing.

“7 To abhor and cease from sin,

Abstinence from strong drink,

Not to be weary in well-doing,—

These are the greatest blessing.

“8 Reverence and lowliness,

Contentment and gratitude,

The hearing of Dharma at due seasons,—

This is the greatest blessing.

“9 To be long-suffering and meek,

To associate with the tranquil,

Religious talk at due seasons,—

This is the greatest blessing.

“10 Self-restraint and purity,

The knowledge of noble truths,

The attainment of Nirvâna,—

This is the greatest blessing.”

THE ONE THING NEEDFUL.

Certain subtle questions were proposed to Buddha, such as: What will best conquer the evil passions of man? What is the most savoury gift for the alms-bowl of the mendicant? Where is true happiness to be found? Buddha replied to them all with one word, Dharma (the heavenly life). (Bigandet, P225.)

“WHOSOEVER SHALL SMITE THEE ON THY RIGHT CHEEK OFFER HIM THE OTHER ALSO.”

A merchant from Sûnaparanta having joined Buddha’s society, was desirous of preaching to his relations, and is said to have asked the permission of the master so to do.

“The people of Sûnaparanta,” said Buddha, “are exceedingly violent; if they revile you what will you do?”

“I will make no reply,” said the mendicant.

“And if they strike you?”

“I will not strike in return,” said the mendicant.

“And if they kill you?”

“Death,” said the missionary, “is no evil in itself. Many even desire it to escape from the vanities of life.” (Bigandet, P216.)

BUDDHA’S THIRD COMMANDMENT.

“Commit no adultery.” Commentary by Buddha: “This law is broken by even looking at the wife of another with a lustful mind.” (Buddhaghosa’s “Parables,” by Max Müller and Rogers, P153.)

THE SOWER.

It is recorded that Buddha once stood beside the ploughman Kasibhâradvaja, who reproved him for his idleness. Buddha answered thus:—”I, too, plough and sow, and from my ploughing and sowing I reap immortal fruit. My field is religion. The weeds that I pluck up are the passions of cleaving to this life. My plough is wisdom, my seed purity.” (“Hardy Manual,” P215.)

On another occasion he described almsgiving as being like “good seed sown on a good soil that yields an abundance of fruits. But alms given to those who are yet under the tyrannical yoke of the passions, are like a seed deposited in a bad soil. The passions of the receiver of the alms, choke, as it were, the growth of merits.” (Bigandet, P211.)

“NOT THAT WHICH GOETH INTO THE MOUTH DEFILETH A MAN.”

In the “Sutta Nipâta,” chapter 2., is a discourse on the food that defiles a man (Âmaghanda). Therein it is explained at some length that the food that is eaten cannot defile a man, but “destroying living beings, killing, cutting, binding, stealing, falsehood, adultery, evil thoughts, murder,”—this defiles a man, not the eating of flesh.

“WHERE YOUR TREASURE IS.”

“A man,” says Buddha, “buries a treasure in a deep pit, which lying concealed therein day after day profits him nothing, but there is a treasure of charity, piety, temperance, soberness, a treasure secure, impregnable, that cannot pass away, a treasure that no thief can steal. Let the wise man practise Dharma. This is a treasure that follows him after death.” (“Khuddaka Pâtha,” P13.)

THE HOUSE ON THE SAND.

“It [the seen world] is like a city of sand. Its foundation cannot endure.” (“Lalita Vistara,” P172.)

BLIND GUIDES.

“Who is not freed cannot free others. The blind cannot guide in the way.” (Ibid. P179.)

“AS YE SOW, SO SHALL YE REAP.”

“As men sow, thus shall they reap.” (“Ta-chwang-yan-king-lun,” sermon 57.)

“A CUP OF COLD WATER TO ONE OF THESE LITTLE ONES.”

“Whosoever piously bestows a little water shall receive an ocean in return.” (“Ta-chwang-yan-king-lun,” sermon 20).

“BE NOT WEARY IN WELL-DOING.”

“Not to be weary in well-doing.” (“Mahâmangala Sutta,” ver. 7.)

“GIVE TO HIM THAT ASKETH.”

“Give to him that asketh, even though it be but a little.” (“Udânavarga,” ch. xx. ver. 15.)

“DO UNTO OTHERS,” ETC.

“With pure thoughts and fulness of love I will do towards others what I do for myself.” (“Lalita Vistara,” ch. v.)

“PREPARE YE THE WAY OF THE LORD!”

“Buddha’s triumphant entry into Râjagriha (the “City of the King”) has been compared to Christ’s entry into Jerusalem. Both, probably, never occurred, and only symbolise the advent of a divine Being to earth. It is recorded in the Buddhist scriptures that on these occasions a “Precursor of Buddha” always appears. (Bigandet, P147.)

“WHO DID SIN, THIS MAN OR HIS PARENTS, THAT HE WAS BORN BLIND?” (John ix. 3.)

Professor Kellogg, in his work entitled “The Light of Asia and the Light of the World,” condemns Buddhism in nearly all its tenets. But he is especially emphatic in the matter of the metempsychosis. The poor and hopeless Buddhist has to begin again and again “the weary round of birth and death,” whilst the righteous Christians go at once into life eternal.

Now it seems to me that this is an example of the danger of contrasting two historical characters when we have a strong sympathy for the one and a strong prejudice against the other. Professor Kellogg has conjured up a Jesus with nineteenth century ideas, and a Buddha who is made responsible for all the fancies that were in the world B.C. 500. Professor Kellogg is a professor of an American university, and as such must know that the doctrine of the gilgal (the Jewish name for the metempsychosis) was as universal in Palestine A.D. 30, as it was in Râjagriha B.C. 500. An able writer in the Church Quarterly Review of October, 1885, maintains that the Jews brought it from Babylon. Dr. Ginsburg, in his work on the “Kabbalah,” shows that the doctrine continued to be held by Jews as late as the ninth century of our era. He shows, too, that St. Jerome has recorded that it was “propounded amongst the early Christians as an esoteric and traditional doctrine.”

The author of the article in the Church Quarterly Review, in proof of its existence, adduces the question put by the disciples of Christ in reference to the man that was born blind. And if it was considered that a man could be born blind as a punishment for sin, that sin must have been plainly committed before his birth. Oddly enough, in the “White Lotus of Dharma” there is an account of the healing of a blind man, “Because of the sinful conduct of the man [in a former birth] this malady has risen.”

But a still more striking instance is given in the case of the man sick with the palsy. (Luke v. 18.) The Jews believed, with modern Orientals, that grave diseases like paralysis were due, not to physical causes in this life, but to moral causes in previous lives. And if the account of the cure of the paralytic is to be considered historical, it is quite clear that this was Christ’s idea when He cured the man, for He distinctly announced that the cure was affected not by any physical processes, but by annulling the “sins” which were the cause of his malady.

Traces of the metempsychosis idea still exist in Catholic Christianity. The doctrine of original sin is said by some writers to be a modification of it. Certainly the fancy that the works of supererogation of their saints can be transferred to others is the Buddhist idea of good karma, which is transferable in a similar manner.

“IF THE BLIND LEAD THE BLIND, BOTH SHALL FALL INTO THE DITCH.” (Matt. xv. 14.)