by Dr. William L. Pierce

IT IS AN ARTICLE of faith among the members of the so-called “radical right” that the Soviet Union today is as firmly under the thumb of a ruling minority of Jewish commissars as it was in the years immediately after the Bolshevik revolution of 1917.

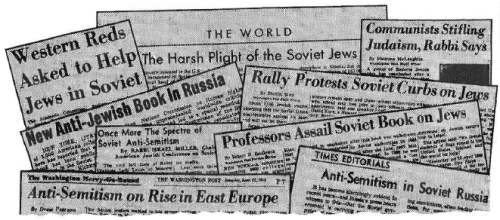

All the wails by world Jewry about “Soviet anti-Semitism,” just as the lukewarm Soviet backing of Israel’s Arab opponents, are seen as pure subterfuge aimed at deceiving the Gentile West as to the true state of affairs behind the Iron Curtain.

It is, on the other hand, an article of faith among nearly everyone else — from “responsible conservatives” to the AFL-CIO’s George Meany to those who take their ideological cues from the New York Times or the Washington Post — that the Soviet Union is run by fanatical anti-Semites who single out Soviet citizens of the Jewish faith for especially harsh persecution.

To question the first article of faith is to lay oneself open to the suspicion of being in cahoots with the Jews, while to question the second is to bring down on one’s head the immediate charge of being an anti-Semite.

The fact is that neither article of faith has any correspondence with reality, as we shall see in what follows. Before we can understand the true situation of the Jews in the Soviet Union today, however, we must understand how that situation has developed and changed during the last few decades. Indeed, it will be helpful for us to look much further back than that.

The Jews of Eastern Europe trace their origins to two principal sources. One of these sources — and by far the more important one for the Jews of Russia — was a Tatar tribe, the Khazars, who moved from Asia into the area north and northwest of the Caspian Sea in the second century. In the eighth century the Khazars converted en masse to Judaism, after their king, Bulan, came under the influence of a traveling Jewish merchant.

Two centuries later the Khazar kingdom was destroyed by Varangian warriors from Scandinavia, who established their hegemony over the Slavic peoples of Russia, Poland, and the Ukraine, but communities of Khazar Jews had already entrenched themselves solidly throughout this area.

The other source was the Jews repeatedly expelled from virtually every country of Western Europe throughout the Middle Ages. During the various expulsions (from England in 1290, from Germany in 1298 and numerous subsequent occasions, from France in 1306, from Austria in 1421, from Spain in 1492, from Portugal in 1497, etc.) the evicted Jews filtered in to other countries which, for the moment, would have them. One of those countries was Poland, which in those days comprised a vast territory including much of the Ukraine and western Russia.

The incoming trickle of part-Semitic Jews from the west amalgamated with the non-Semitic Khazar Jews already in Poland, with the Khazar element predominating. Thus, when Russia annexed huge sections of Poland in the 18th century, she also acquired a substantial infestation of these racially mixed Polish Jews.

Both Jewish elements were racially, culturally, and spiritually alien to the Gentile Russians, and a deep-seated hostility between Jews and Russians was established from the time they first came in contact. Relations between the two races were not helped by the tendency of the Jews to monopolize trade, to ingratiate themselves with the nobility at the expense of the peasantry, and, in general, to soak up all the available money of the country.

Remembering that prior to the 18th century much of what is now Russia was Poland, we can get an idea of Jew-Gentile relations there from the Jewish historian Abram Sachar’s widely read History of the Jews. Sachar writes:

“…All through the twelfth century Jews (in Poland) prospered as merchants, traders, and tax-farmers. Many of them were in charge of the mints, and the Polish coins sometimes bore the names of the princes in Hebrew characters! After… the middle of the thirteenth century… the Jews… became the only commercial class in a country of landlords and peasants.”

Four hundred years later, in the 17th century, “Jews continued to serve the nobles as tax-collectors, tax-farmers, financiers, and particularly stewards and overseers of their estates. But these positions, while adding to their power, increased popular animosity. The peasants, who were being exploited by the nobles, hated the tools of tyranny more than tyranny itself.”

Indeed, the Russian peasantry hated the Jews so intensely that, for the sake of keeping down public unrest, the tsars strictly limited the area of the country within which Jews were allowed to settle. That area, the Pale of Settlement, comprised much of western Russia and was the scene of nearly continuous conflict between its Jewish and its Russian inhabitants.

Throughout the 19th century a series of tsars attempted to alleviate Russia’s festering Jewish problem by assimilating the Jews into the mainstream of Russian society. The Jews, however, bitterly resisted every effort to “Russianize” them. They refused to work on the land or to engage in manual labor, and they continued to use two languages: Russian for doing business with Gentiles, and Yiddish for talking to one another.

The efforts of the tsars — notably Alexander I (1801-1825), Nicholas I (1825-1855), and Alexander II (1855-1881) — did have two important effects, however. One of these effects was a great increase in revolutionary activity among Russia’s Jews. One conspiracy after another was hatched against the Russian government, leading to numerous public disturbances and assassination attempts. In 1881 one of these conspiracies culminated in the successful assassination of Tsar Alexander II.

By the end of the 19th century, virtually every Jew in Russia was committed to one or the other — or both — of two far-reaching movements intended to upset the existing order and replace it with one more congenial to Jews. These movements were Marxism and Zionism.

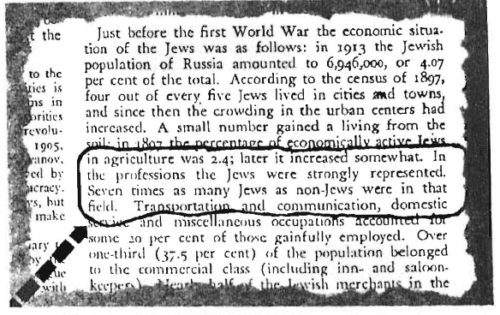

The other effect of the tsars’ efforts — which included compulsory schooling for Jews — was that the Jews began extending their range of activities to include the professions (medicine, law, teaching) as well as commerce. In accord with their usual practice, they attempted to monopolize these new fields of endeavor for themselves, and they very nearly succeeded. The Russian census of 1897 revealed that Jews occupied seven out of every eight professional positions. This insured a passionate anti-Semitism on the part of the small but growing number of middle-class Russians, who found their sons elbowed out of the admission lines to Russia’s medical and law schools by Jews.

As the 20th century dawned, Russia found herself saddled with approximately half of the world’s Jews — nearly seven million of them — all bitterly opposed to the government and in turn bitterly hated by the great masses of Russian people among whom they lived. The Russian secret police — the Okhrana — made strenuous efforts to halt Jewish subversive moves, but the Jews used their connections with Jews outside Russia to great advantage in this regard. As just one example, Iskra (which means “spark”), the newspaper of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party, which later became the Communist Party, was edited and printed by Jews in Munich, Germany, and then smuggled into Russia. Other Jews from Russia carried on their revolutionary activities in Switzerland, the Netherlands, the United States, and other places beyond the reach of the tsars’ police.

Prior to 1900 nearly all the adherents of the various Marxist revolutionary factions in Russia were Jews. Because of the strong hostility which existed between the Jews and the Russian population, the overwhelming Jewishness of the revolutionary movement constituted a major obstacle to the spread of Marxism among Russian workers. With the delegates to the various Marxist congresses which were held between 1900 and 1907 more often addressing their audiences in Yiddish than in Russian, it is easy to understand why not many Russians were attracted to the movement.

After the events of 1905, which included a great deal of popular unrest stemming from Russia’s humiliating defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, a conscious effort was made to bridge the gap between Jewish Marxists and their potential Russian recruits by promoting those few Russian Marxists already in the revolutionary ranks to leading positions. One who benefited some years later from this effort was Josef Djugashvili (actually not a Russian, but a Georgian), a young man unknown outside communist ranks even as late as 1917, but who would later be known to the world as Josef Stalin.

A much more important Marxist than Stalin in the early years was another man generally regarded as a Russian, although he was actually one-quarter Jewish, at least one-quarter Kalmuck (Mongol), one-quarter German, and at most one-quarter Russian, with his Kalmuck heritage showing up most strongly in his face. His name was Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, but he is much better known by his underground pseudonym, “Lenin.”

A number of competent historians have recorded the struggles between the various Marxist factions in Russia and between the Marxists and the Russian government which led to the eventual triumph of Lenin’s Bolshevik faction over all his competitors and, finally, over the government. No attempt will be made here even to summarize these struggles. Frank L. Britton’s little booklet, Behind Communism, is recommended to the reader who wants to delve further into this interesting subject.

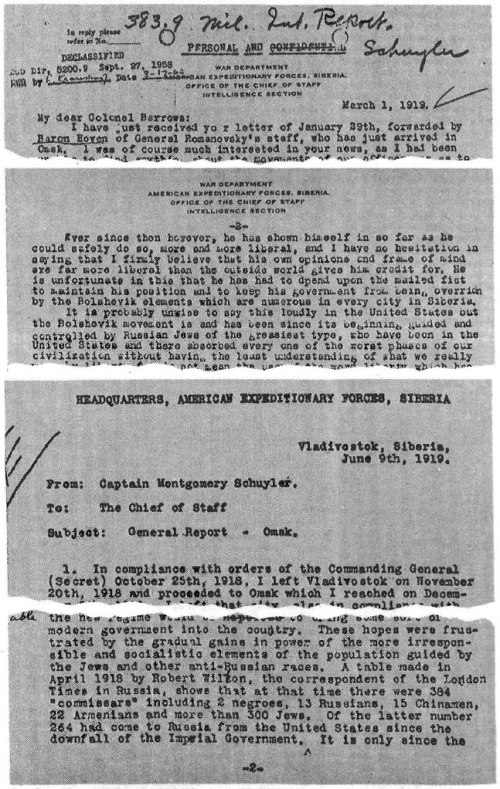

Despite the efforts to “Russianize” the Communist Party, both before and after the 1917 revolution, the leadership cadres remained overwhelmingly Jewish until the late 1930s. One organ of the Soviet regime in particular which was notoriously non-Russian was the secret police, known by a sequence of acronyms and initials which soon came to strike terror into the heart of every Russian: Cheka, GPU, OGPU, NKVD, NKGB, MGB, KGB.

The masses of the Russian people, in fact, were so much outsiders to the various Marxist factions squabbling over the corpse of tsarist Russia that the greatest danger faced by the early Bolshevik commissars was a bullet in the back from another Jew — not from a Russian. Thus, Moses Uritsky, the bloodthirsty Cheka boss of Petrograd, was murdered on August 30, 1918, by the Jew Kanegiesser, a member of the Social Revolutionary faction. And on the same day Lenin was critically wounded by bullets fired at him by Fanny Kaplan, another Social Revolutionary — and a member of a long line of Jewesses who have turned to political assassination, the latest in this line being Sara Kahn (usually identified in the controlled news media by her pseudonym, “Sara Jane Moore”).

Lenin recovered from Fanny Kaplan’s bullets, but he died on January 21, 1924, from a stroke, following a long illness. During Lenin’s last years the most powerful communist in Russia was easily Lev Trotsky (born Bronstein), the Jewish commissar of the Red Army.

Trotsky’s chief rival was to be Stalin, who became General Secretary of the Communist Party in March 1922. Stalin was a cleverer political infighter than Trotsky. In order to bring down Trotsky he allied himself with Jewish Politburo members Lev Kamenev (born Rosenfeld) and Grigori Zinoviev (born Apfelbaum). Within a year after Lenin ‘s death the Stalin-Kamenev-Zinoviev triumvirate had successfully outflanked Trotsky.

And, although Zinoviev outranked Stalin at the time of Lenin’s death, it did not take Stalin but a few months after he and his allies had undermined Trotsky’s position for him to gain the upper hand over both Kamenev and Zinoviev. By 1927 Stalin had emerged as the virtual dictator of the Soviet Union.

Stalin’s rise to supremacy did not go undisputed, however. Even after 1927 various individuals and coalitions of communists made the fatal mistake of attempting to unseat him. Stalin was able to maintain and consolidate his power only because he possessed extraordinary skill in the cut-throat game of conspiracy and counter-conspiracy which raged in the Communist Party hierarchy for more than a decade after the revolution. In cunning, ruthlessness, suspiciousness, and deviousness he was a match for any Jew in Russia.

The attitudes and patterns of thought formed during the early years of vicious infighting stayed with Stalin all his life. He never lost the feeling that he was surrounded by enemies who were conspiring against him, and until his death he continued to employ the divide-and-rule tactics which enabled him to claw his way to the top.

The series of arrests and show trials of the late 1930s, known as “the Great Terror,” were primarily a manifestation of Stalin’s paranoia. During the years of the Great Terror Stalin more-or-less continuously purged and repurged the Communist Party, destroying in the process all enemies, both real and imaginary, and liquidating all factions, actual or potential, which might conceivably challenge his rule.

It is true that during the years 1937-1939 a great many Jewish communists were killed, and that when the smoke had cleared there were fewer Jews and more Russians in the upper ranks of the party than before. Stalin’s purges can in no way be interpreted as an anti-Semitic move, however. Jewish party members were liquidated, not because they were Jews, but because every party official was regarded as a potential threat by Stalin. More often than not the secret police official who fired the fatal bullet into the back of the Jewish victim’s head in the cellars of the NKVD was himself a Jew.

And Russians also were killed in droves during the purges — in far greater numbers, in fact, than Jews. And, although the liquidation of so many high-ranking officials brought a flux of non-Jews up from the lower ranks of the hierarchy as replacements, Jews still remained by far the largest ethnic group in the Soviet power structure at the outbreak of World War II.

When Hitler launched his blitzkrieg attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, determined to stamp out the menace of Jewish Marxism once and for all, Stalin’s worries turned in a new direction. The Jews, not only in Russia but everywhere, had suddenly become his most important allies in the death struggle with Hitler.

As soon as the Germans invaded the Soviet Union Stalin could count on the moral backing of Jewry everywhere. More importantly, with their enormous power of the press and of the purse, they could insure him the material support of the United States government.

The behavior of the Jews in the USSR in the early days of the war caused him considerable worry, however. As the Germans advanced, tens of thousands of Russia’s Jews loaded their suitcases with currency and headed for the Far Eastern provinces, where they immediately went into business as black marketeers. This had a very bad effect on the morale of the Russian masses, who were being exhorted to sacrifice everything in the fight against the fascist invaders.

Stalin kept the problem in check by having a few hundred Jewish currency speculators and black market dealers publicly shot, but he could hardly afford to take any stronger measures against them, or the Jews in America and Britain might simply call off the war, and he would be left alone to deal with Hitler.

World War II convinced Stalin of one thing: he could never again feel safe against external enemies with the Soviet bureaucracy in the grip of a people who had no fundamental loyalty to Russia, like the pharaoh who “knew not Joseph,” he asked himself whether it might not happen that “when there falleth out any war” — a war against a philo-Semitic power instead of an anti-Semitic one next time, perhaps — Russia’s Jews would “join also unto our enemies.” He began taking steps to remedy this dangerous situation as soon as the war was over.

Acting with great discretion at first, Stalin started weeding Jews out of the upper levels of the Soviet hierarchy. It was necessary to proceed slowly for two reasons.

First, Jewish communists in the United States, Canada, and Britain were still funneling very valuable atomic and military secrets to him. Like U.S. atom-spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Jews everywhere still regarded the Soviet Union as a Jewish paradise.

Second, Soviet society was utterly dependent upon its Jewish managers and technocrats for its continued functioning. For three decades Jews had virtually monopolized the bureaucracy and the professions, and it was necessary to train a new generation of Russians to replace them.

After the Zionist seizure of Palestine in 1948 — which was immediately given an official blessing by the Soviet Union — Stalin greatly accelerated his weeding-out program. Zionism — loyalty to a foreign power — was equivalent to treason, and every Jew, whether he professed loyalty to Israel or not, was regarded as at least a potential Zionist.

Between 1948 and 1953, Stalin’s changed attitude toward the Jews filtered down to the Russian masses. On the law books anti-Semitism was still equivalent to anti-Sovietism — an equivalence established by Lenin’s infamous edict of August 9, 1918 — and, as revealed by Solzhenitsyn in his First Circle, an ordinary Russian could still be given a 10-year sentence at hard labor for casually using the word “zheed” (kike) — but, at least, one was no longer shot for such an offense, as was the case before the war. A few bold Russians defied the law, and poems, short stories, and a few pamphlets began circulating surreptitiously, which reflected, for the first time in 30 years, the deep-smoldering resentment of the people against the Jews.

In Romania, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and other Soviet satellites Stalin’s program was also underway. The Soviet-puppet governments which had been installed in these countries in the wake of their “liberation” by the Red Army were almost completely “kosher.” Now the Jewish party bosses and commissars — Ana Pauker in Romania, Rudolf Slansky in Czechoslovakia, Matyas Rakosi in Hungary — were being summarily deposed and replaced by Poles, Czechs, Hungarians, etc.

The Senate Judiciary Committee issued the above report in 1965. Its purpose was to show that the Jews are being “discriminated against” by the Soviet government, but in doing so it inadvertently revealed that the Jews had formerly constituted more than 40 per cent of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR! The extract is from page 63 of the report.

It was in this period — the period of the “Cold War” — that Jews began their public wailing about “Soviet anti-Semitism.” In fact, there is a fundamental connection between Stalin’s weeding-out program and the onset of the Cold War. It was the postwar recognition by the Jewish masters of America’s mass media that their fortunes had changed in the USSR that led to a deliberate effort on their part to shift American public opinion and governmental policy away from the pro-Soviet stance which they themselves had generated during World War II. But that is another story in itself.

Stalin died on March 5, 1953. There are persistent rumors that his death came just on the eve of a planned roundup of all the remaining Jews in the Soviet Union — and that it was Stalin’s plan for this “final solution” of Russia’s Jewish problem which led to his death by poison at the hands of one of his associates or doctors. At this time we have no way of knowing the truth of the matter. We do know, however, that Stalin’s program to Russify the upper ranks of the Soviet bureaucracy had been largely accomplished by the time of his death.

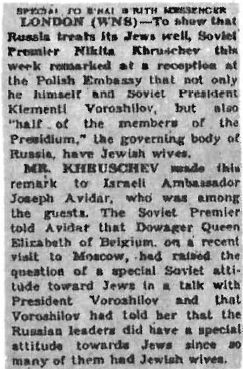

With Stalin dead the Jews of Russia were out of any danger of being abandoned by the Soviet government to the wrath of the Russian people. During the period of “de-Stalinization” which followed, most of Stalin’s measures against the Jews were relaxed. But the government was not handed back over to the Jews. Russian communists were in the saddle now, and they intended to stay there.

And thus it has continued to the present. And the Jews in the United States and other Western countries maintain their nonstop serenade of the Gentile public with tales of woe and persecution in the USSR.

Undoubtedly, many Jews actually believe they are being persecuted by the Soviet government. After all, are they not God’s “chosen people,” who by right should rule over the Russians? Is it not “persecution” to deny them this right?

In any event, believed by the Jews or not, this serenade is largely believed by their gullible Gentile audience, and it serves as a very useful means of maintaining the pressure of Western public opinion against the Soviet government. As long as the Soviets are dependent upon trade with the West, they are obliged to tread lightly where Soviet Jews are concerned.

Thus, Henry Kissinger’s policy of detente (rather, partial detente, the prospect of detente), which is facetiously attacked by many American Jews and their Gentile henchmen (Senator Jackson, for example) actually serves the Jews very well. It insures that their present position in the Soviet Union will not deteriorate further, as it did under Stalin. And what is that position today?

Jews, who today account for just under one per cent (0.9) of the total population of the Soviet Union, occupy approximately the same percentage (0.8) of senior party and government positions in that country.

But Jews constitute 1.9 per cent of all students and 5.5 per cent of all faculty members at Soviet institutions of higher education. They account for 7 per cent of all Soviet scientists. They hold 14 per cent of the doctoral degrees in the Soviet Union. And they make up more than 20 per cent of the highly paid members of the performing arts, entertainment, and mass communications professions. These figures (except the last) are from the May 1974 issue of Commentary, a magazine published by the American Jewish Committee, which is in the forefront of those organizations lamenting the “persecution” of Soviet Jews.

The truth is that Jews are not now and never have been persecuted by a communist government. They constitute a privileged minority in the Soviet Union today, a minority which holds a higher percentage of soft jobs and enjoys a higher standard of living than any other ethnic group — including Russians — and which is the only minority which has been allowed to emigrate.

It is also true that Jews in the Soviet Union are not as privileged a group today as they were before World War II. But Stalin did not persecute Jews when he curtailed some of their privileges; he simply set out to correct the gross inequity which existed in the Soviet Union between the power wielded by Jews and that wielded by Russians and other ethnic groups. It is this long-overdue correction which the Jews of the world so indignantly refer to as “persecution.”

Today’s Soviet leaders are not passionate men, not idealistic men, not religious men. They are not the sort of men burning with a sense of justice, with a craving to right old wrongs and settle old scores. They are not the sort of men, in short, to persecute Jews, for what is the profit in that?

They are cold-blooded businessmen-gangsters, not basically unlike the sort we are familiar with in this country. They do what is necessary to protect their power, but they do not waste their time and energy on such trifles as justice.

But the day may come when the Russian masses will rise up and throw off the communist yoke which was put on their necks nearly 60 years ago. If that day does come, then the Jews will really have something to scream about.

From Attack! No. 43, 1976

transcribed by Vanessa Neubauer from the book The Best of Attack! and National Vanguard, edited by Kevin Alfred Strom

imgnv

COPYRIGHT ©1970-2019 NATIONALVANGUARD.ORG, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. OPINIONS EXPRESSED HEREIN ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF NATIONAL VANGUARD OR ITS EDITORS, OR ANY OTHER ENTITY. SOME CLEARLY MARKED MATERIALS ARE PARODIES OR FICTION. SOME ITEMS ARE PUBLISHED BASED ON FAIR USE FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES. BY SUBMITTING MATERIAL YOU GRANT US AN UNLIMITED NON-EXCLUSIVE LICENSE TO USE THE MATERIAL. DOWN THESE MEAN STREETS A MAN MUST GO WHO IS NOT HIMSELF MEAN, WHO IS NEITHER TARNISHED NOR AFRAID.

https://archive.is/4tKbr#selection-707.0-707.29